The story of Israel can be described as the story of the Jewish people in the modern era. Many young people have been inspired by Herzl’s phrase “If you will it, it is no dream” but what is the story behind the roots of Zionism? How did the yearning for the Jewish people to live in their own land move from that dream towards a reality? What is perhaps one of the incredible, special aspects of Zionism is how both the grassroots and the political leadership established themselves almost simultaneously and independently of one another.

On the ground there were pioneers from Eastern Europe, mainly from Russia, making their way to Ottoman Palestine to eke out a living and build Jewish settlements from the 1880s. Martin Gilbert charts their progress in his book Israel a History. He says:

25,000 Jews reached Palestine between 1882 and 1903. Known as the First Aliyah, from the Hebrew word for ascent.

Join the fight for Israel’s fair coverage in the news

Then a man called Theodor Herzl enters into the story:

One of those who had little knowledge of what had already been achieved in Palestine, especially by the Russian immigrants of the previous two decades, was a Hungarian-born Jew, Theodor Herzl. As a journalist in Paris since 1891, he was shocked by the anti-Semitism in France at the time of the Dreyfus case, when a Jewish officer was found guilty of treason, a charge later found to have been false. The harsh anti-Semitic tone of much of the criticism of Dreyfus appalled Herzl who also knew of the suffering of Jews in Russia. His calls for a return to Zion appealed above all to the Jews of Russia, for hundreds of thousands of whom the United States had hitherto been the main possible place of refuge and renewal.

The Dreyfus trial was a watershed in Jewish history. Jews everywhere asked themselves what had gone wrong with Jewish life. Why was there anti-Semitism? Three ways out of the trap seemed to present themselves: to become assimilated into the nation with whom one was living, to fight for a revolutionary socialism that would cure all the evils of the world including anti-Semitism, or to seek a ‘normal’ Jewish life in a Jewish land with a Jewish government. Herzl was drawn to the last option.

With Herzl’s formation of the World Zionist Organization, the grassroots and the political leadership were brought together to form a movement whose success soon had an air of inevitability. Note that the political leadership in the form of Herzl was motivated by the antisemitism of Western Europe, embodied in the Dreyfus trial whereas the grassroots came from Eastern Europe and was motivated by the antisemitic experiences of the Jews of Russia and Romania.

For Jews during this period, life in Europe was already untenable and as a result Jews were on the move. According to Joellyn Zollman PhD:

Eastern European Jews began to immigrate to the United States in large numbers after 1880. Pushed out of Europe by overpopulation, oppressive legislation and poverty, they were pulled toward America by the prospect of financial and social advancement. Between 1880 and the onset of restrictive immigration quotas in 1924, over 2 million Jews from Russia, Austria-Hungary, and Romania came to America.

In comparison to the numbers of Jews leaving Eastern Europe for the USA, the numbers of Jews moving to Ottoman Palestine were tiny. However the impact of the ideal of a Jewish state cannot be measured in numbers of Jews moving to Palestine in isolation. The idea traveled to the USA with the Jews of Russia and there and all over Europe, from London to Saint Petersburg, Herzl was mobbed wherever he went – thousands wanted to hear him speak. For example according to Gilbert:

The Jews of Russia that he had not abandoned them, Herzl secured to their applause an end to the ban on Zionist organizations and fund-raising. Returning to Vienna through Vilna, he was greeted by a vast, admiring mass; so great was the throng at the railway station that gathered to see him off at the end of his visit that they were beaten back by the Tsarist police with considerable brutality.

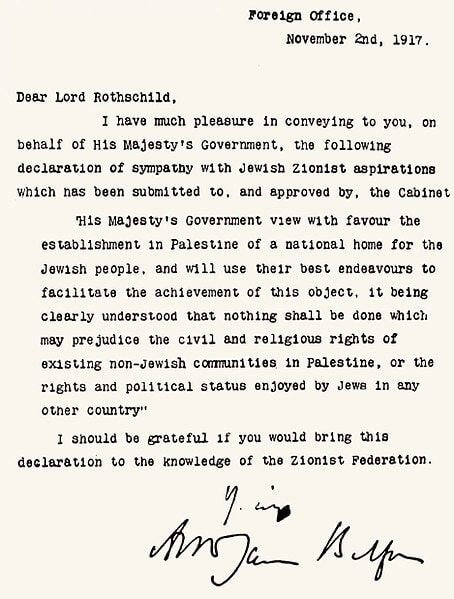

The Balfour Declaration

Over the course of the First World War, the first great milestone of Zionism was overcome in the form of the Balfour Declaration. This declaration made by the British colonial minister Lord Arthur Balfour, for the first time gave Zionism the kind of diplomatic recognition from a great power that it needed. Martin Kramer wrote of this declaration that:

The Balfour Declaration, for all its vagaries, constituted the first step toward the objective of political Zionism as outlined by the First Zionist Congress at its meeting in Basle, Switzerland in 1897: “Zionism seeks to establish a home for the Jewish people in Palestine secured under public law.” Theodor Herzl had failed to land such a commitment, either from the Ottoman sultan or from any of Europe’s potentates. The declaration was the much-awaited opening: narrow, conditional, hedged, but an opening all the same.

With the Balfour Declaration and what was once Ottoman Palestine becoming the British mandate of Palestine, the Zionist movement moved ever closer to the goal of an autonomous Jewish state. The grassroots spent the early years toiling in the fields and founding the first settlements, places whose names are now synonymous with modernity. Tel Aviv, the first Jewish city was founded in 1909 and the Hebrew University was established in 1918. The pioneers of Zionism were farsighted enough to foresee the end of Jewish life in Europe. In 1938, Ze’ev Jabotinsky said of the Jews in Poland that they were “living on the edge of the volcano.”

Through the efforts of the early pioneers the infrastructure that would later support waves of aliyah was built. The solid roots of Zionism ensured that the state of Israel grew in fertile soil and blossomed into the economic and military powerhouse it is today.