Failed Israeli-Palestinian peace plans litter the diplomatic landscape like the rusted hulks of old blown out military vehicles dotting forlorn and forgotten battlefields.

Of course, peace plans aren’t limited to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Other initiatives have attempted to reconcile Hamas and Fatah or address conflicts involving Syria, Lebanon, Cyprus, Turkey, Iraq and the Kurds.

While most proposals to resolve the Israeli-Palestinian never gained traction, two continue to influence the peace process to this day. A closer look at the 1967 Allon Plan and the 2002 Saudi Initiative offers some perspective on today’s peacemaking efforts, how the peace process got to where we are today and what any future Israeli-Palestinian peace plans can learn.

For brevity’s sake, the 1993 Oslo accords will not be addressed here either. Readers are referred to The Oslo Accords: Searching For Peace. And as of this writing, it is too early to gauge whether President Donald Trump’s peace proposal will have a lasting impact. (Other initiatives, such as the 1991 Madrid Conference and the 2002 Road Map to Peace sought to create frameworks for Israelis and Palestinians to talk, not propose final outcomes as the Allon Plan and the Saudi Initiative did.)

Related reading: The Oslo Accords: Searching for Peace

Join the fight for Israel’s fair coverage in the news

The Allon Plan

Drafted by: Yigal Allon

Drafted by: Yigal Allon

When: June 1967 following the Six-Day War

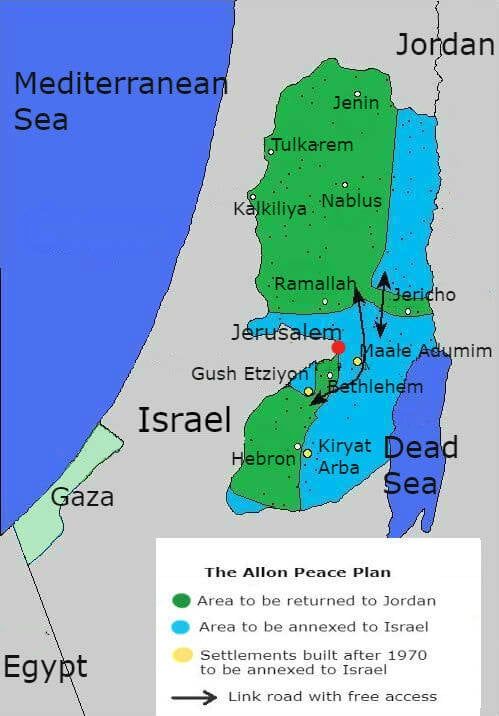

What it proposed: Allon suggested Israel to annex the Jordan Valley, the Gush Etzion bloc and eastern Jerusalem, about one-third of the West Bank. The northern and southern areas of the West Bank would become a Palestinian autonomous territory.

Their territory was separated by greater Jerusalem, which Allon didn’t consider open for discussion. The plan instead proposed link roads and a corridor for Palestinian access to Jordan.

By 1968, Allon gave up on Palestinian autonomy and proposed transferring those areas to Jordan to create a Jordanian-Palestinian state, but King Hussein rejected the idea. While Allon wanted to return the Sinai Peninsula, he initially wanted to annex the Gaza Strip. The Allon Plan was later revised to make Gaza part of a Jordanian-Palestinian state.

Allon also wanted to establish an autonomous Druze republic in the Golan Heights and Syria’s adjacent Suwayda region. But the idea of a Druze buffer state never gained traction among Israeli policymakers.

Allon was one of the founding members of the Haganah’s elite Palmach forces during Israel’s pre-state years and was one of the heroes of the War of Independence. In 1969, Allon served as caretaker prime minister for a month following the death of Levi Eshkol. In the mid-1970s, Allon was Israel’s foreign minister. He died in 1980.

The plan’s significance: The Allon Plan was based on the doctrine that Israeli sovereignty over a large part of the West Bank was necessary for Israel’s defense.

Most critically, the Allon plan reflected the unwillingness of Israeli leaders to absorb the West Bank’s Palestinian population into Israel so as not to upset the Jewish state’s demographic balance. Thus, Allon wanted to return populated areas and most of the Sinai Peninsula to Arab control. He sought to include as few Arabs as possible in areas claimed by Israel.

Immediately after the Six-Day War, Israel offered to negotiate with the Arabs on the basis of land-for-peace. But the Arab League rejected peace in what became known as The Three Noes (No peace with Israel, no recognition of Israel and no negotiations with Israel). Although no Israeli government ever formally adopted the Allon Plan, it has for years served as a guideline for Israeli policy in the West Bank and Gaza.

Related reading: Three Noes That Set the Middle East On Course of Conflict

The Arab/Saudi Peace Initiative

Drafted by: First floated by Saudi Crown Prince Abdullah, it was adopted by the Arab League. The names Arab Peace Initiative and Saudi Peace Initiative are often used interchangeably. Abdullah became king in 2005 and advocated the plan during his 10-year reign.

When: The plan was launched at the Arab League summit of 2002 in Beirut, but was overshadowed by the Passover Massacre in Netanya, in which a Palestinian suicide bomber killed 39 people and injured 140 more.

What it proposed: It calls for the state of Israel to withdraw its forces from all land captured during the Six-Day War, recognize an independent Palestinian state in the West Bank and Gaza with East Jerusalem as its capital, and a negotiated “just solution” for Palestinian refugees. In return, the Arab states affirmed they would consider the conflict over, recognize Israel and establish normal relations.

At face value, the proposal sounds like a straightforward acceptance of land for peace and paradigm shift from The Three Noes of 1967. But Israel chose not to respond to the Saudi initiative. Mitchell Bard explains some of the reasons:

In fact, the “new” initiative is nothing more than a restatement of the Arab interpretation of UN Resolution 242. The problem is that 242 does not say what the peace plan calls on Israel to do. The resolution calls on Israel to withdraw from territories occupied during the war, not “all” the territories in exchange for peace. In fact, the Arab delegates lobbied to have the word “all” included in the resolution and this idea was rejected.

In addition, Resolution 242 also says that every state has the right to live within “secure and recognizable boundaries,” which all military analysts have understood to mean the 1967 borders with modifications to guarantee Israel’ security. Incidentally, the resolution does not say that one comes before the other, rather, they are equal principles. Israel is under no obligation to withdraw before the Arabs agree to live in peace . . .

The refugee issue was not part of Abdullah’s original proposal and was added at the summit under pressure from other delegations. Also, it is important to note that Resolution 242 says nothing about the Palestinians and the reference to refugees can also be applied to the Jews who fled and were driven from their homes in Arab countries. Another change from Abdullah’s previously stated vision was a retreat from a promise of full normalization of relations with Israel to an even vaguer pledge of “normal relations.”

Joshua Teitelbaum elaborated on the initiative’s “all or nothing” approach, which made the initiative unsuitable to even serve as a basis for future talks, amounting to “negotiations by diktat.”

The plan’s significance: It is actually surprising that the Saudi Initiative still has legs today. The Palestinian terror attacks of the Second Intifada simply made peace negotiations impossible. By the time the suicide bombings and shootings finally subsided due to a combination of Israel’s security barrier and Palestinian exhaustion, Israeli attitudes towards peace had hardened.

Moreover, the Iranian threat to the Middle East has changed the region’s geopolitical calculus. Israeli-Saudi relations are thawing despite the lack of progress on the Palestinian track. Israeli blogger Alex Lapshin visited the desert kingdom and “the Saudis he met all knew he was from Israel, showed interest in the country, and were overjoyed by the newly developing relationship between the two countries.”

However, despite its flaws, the Saudi initiative is a step beyond the Three Noes. Its unanimous approval by the Arab League means it enjoys a rare Arab consensus support. And it’s difficult to imagine any new Israeli-Palestinian peace plans being put forward by the Arab world. So the Saudi Initiative remains, for better or for worse.

Related reading: Israel-Saudi Arabia Relations in Focus

Other Israeli-Palestinian Peace Plans

Other proposals to solve the Israeli-Palestinian conflict had their 15 minutes of fame before fading. These peace plans fell to the wayside because their architects lacked sufficient influence (though changing political circumstances accelerated the collapse of Ehud Olmert’s short-lived plan). Among them:

- The Isratin Proposal for a one-state solution, most notably adopted by Libyan dictator Muammar Gadaffi.

- The Israeli Peace Initiative of 2002, whose 40 signatories were Israeli security personalities affiliated with the Left.

- The Geneva Initiative of 2003 drafted primarily by Yossi Beilin and Yasser Abed Rabbo.

- The “Populated Area-Exchange Plan” of 2004 floated by Avigdor Liberman.

- The Palestinian Prisoners Document of 2006.

- The Realignment Plan of 2006 shaped by prime minister Ehud Olmert.

* * *

Only time will tell if the Trump peace proposal will have a lasting impact.

But the continuing influence of the Allon Plan and the staying power of the Saudi Initiative give a clear picture of the basic elements of any future peace plans or negotiated settlement: a two-state solution resulting from direct Israeli-Palestinian talks that takes Israeli security needs into account and is backed by Arab consensus.

Enjoyed reading this article? Follow the Israel In Focus page on Facebook to read more articles explaining Israel’s history, politics, and international affairs. Click here to learn more!

Featured image: CC BY Ray MacLean; Allon map via Wikimedia Commons with improvements by HonestReporting; Abdullah via Wikimedia Commons; flags and vectors CC0 Pixabay;