Few words are as well-known to Jews around the world as the lyrics of Hatikvah, Israel’s national anthem. Meaning “the hope,” the anthem echoes 2,000 years of Jewish prayers for an end to exile and the return of the Jewish people to Zion.

But the song is not without controversy.

Theodor Herzl despised the song and tried to replace it. Zionists of religious and secular socialist stripes advanced their own songs as well. All failed because Hatikvah enjoyed an unusually broad grassroots support. Since Israel’s founding, Palestinians have branded it as a racist song while Arab countries hosting athletic events refused to play the anthem for Israeli medalists.

A national anthem is a patriotic song or wordless musical composition reflecting a nation’s history, traditions and struggles. Simply put, it unites citizens and reminds people of the nation’s shared values and aspirations.

Anthems rarely rise completely above dissension, though. In the US, football player Colin Kaepernick stoked controversy by kneeling during the Star Spangled Banner. Australia’s anthem is often criticized for not being inclusive of its Aboriginal population. Attempts to add lyrics to Spain’s anthem proved too divisive. Ireland has two national anthems because one was considered too militaristic.

Join the fight for Israel’s fair coverage in the news

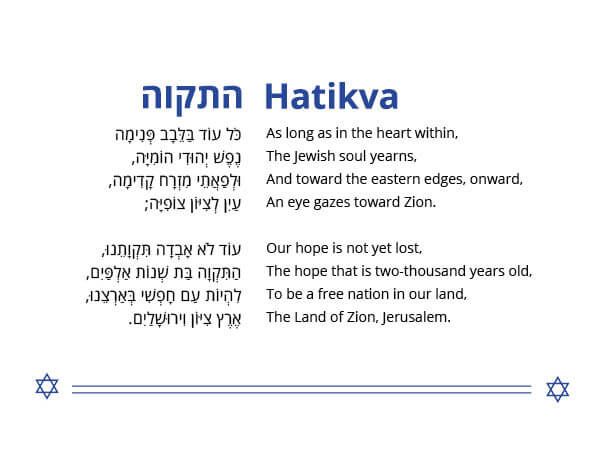

The Lyrics of Hatikva

The significance of Hatikvah or its related controversies cannot be appreciated without first seeing the lyrics and understanding the story behind the anthem.

Origins of the Anthem

The lyrics for Hatikvah were written by poet Naftali Herz Imber. He was born in 1856 in the Galician town of Zloczow (then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, today part of Ukraine). A child prodigy, his poetry earned Imber an award from Emperor Franz Joseph at the young age of 10.

In 1882, during the period known as the First Aliyah, Imber moved to Ottoman Palestine, working as a secretary for Sir Laurence Oliphant, a Christian Zionist author and diplomat.

The words making up Israel’s national anthem were originally part of a nine-stanza poem called Tikvateinu (Our Hope). It’s not known when Imber first began writing Tikvateinu. Scholars speculate that he was inspired by the founding of the the first modern Jewish agricultural settlement, Petach Tikvah, in 1878, or by the prophet Ezekiel’s Vision of the Dry Bones (Ezekiel, ch. 37).

Tikvateinu wasn’t published right away, but Imber enjoyed visiting communities of halutzim (pioneers) where his poetry — especially Tikvateinu — was well-received. Thus, the seeds of Israel’s national anthem began to bud at campfire poetry readings at the earliest agricultural settlements such as Rishon LeZion, Zichron Yaakov, Rosh Pina and Petach Tikvah.

However, its nine stanzas were an unwieldy length; over time, the first two stanzas gradually became the Zionist movement’s unofficial anthem. A number of leading Zionist figures, including Theodor Herzl, disliked both Hatikvah and Imber. In 1897, Herzl went so far as to launch a competition for a new Zionist anthem, but the submissions were so bad, Herzl reportedly had them all burnt.

But the lyrics of Hatikvah had too much grassroots popularity both in the yishuv (the Jewish community of pre-state Israel) and the diaspora.

The full Tikvateinu was published in Imber’s book of poems, Barkai (Morning Star) in 1886.

Imber moved to London in 1887 and later on to the United States. He died penniless in 1919, at the age of 53 of alcohol-induced liver failure and was buried in New York. In 1953, Imber was reinterred in Jerusalem’s Har HaMenuhot Cemetery.

Related reading: The Hebrew Language and the State of Israel

The Italian Melody

So much for the lyrics of Hatikvah. But what of its tune?

Hatikvah’s musical adaptation is credited to Samuel Cohen. Born and raised in Moldavia-Romania, Cohen settled in Rishon LeZion during the First Aliyah.

The melody’s roots actually trace back to the 16th century Italian song, “La Mantovana” (Mantua Dance) by Giuseppe Cenci (also known as Giuseppino del Biado).

Variations of Cenci’s tune multiplied around Europe long before the lifetime of Cohen and Imber. Among La Mantovana‘s recognizable iterations are the Flemish Ik zag Cecilia komen, the Ukranian Kateryna Kucheryava, the Scottish “My mistress is prettie,” the Czech Die Moldau and the Romanian “Carul cu boi. Cohen was presumably influenced by the Romanian version. (In 1919, when the British Mandate began banning broadcasts of Hativkah, Jewish radio instead aired Die Moldau.)

Hatikvah clearly made an impact on the Jewish world.

[Israel Story podcaster Zev] Levi recounts that at the Sixth Zionist Congress, in Basel, in August 1903, the Uganda Proposal to create a temporary Jewish State in East Africa was discussed. The proposal passed, 295 in favor, 178 against.

Its opponents then got up and sang Hatikvah – “the eye looks toward Zion.” Thus, Levi observed, “a Hebrew poem penned by a misfit and stuck to a random Romanian tune, became the unlikely political anthem of a country that did not yet exist”

After World War II, BBC reporters Richard Dimbleby and Patrick Gordon Walker recorded Holocaust survivors singing an emotional rendition of the anthem in Bergen Belsen on the first Sabbath after the death camp’s liberation. (Astute listeners will note however, that their lyrics do not match Hatkivah’s lyrics word-for-word.)

For more in-depth treatment of the musicology and lyrics, see Hatikvah: Conceptions, Receptions and Reflections by Hebrew University Professor Edwin Seroussi.

Alternative Zionist Anthems?

As Hatikvah was first making the rounds, another song — also written by Imber — served as an unofficial anthem of the pioneers. Although it would be overtaken by Hatikvah, some stalwart halutzim refused to let go of Mishmar HaYarden (Watch on the Jordan).

Religious Jews objected to the anthem’s lack of references to God or the Torah. Rabbi Abraham Isaac HaKohen Kook, regarded by many as the godfather of religious Zionism, wrote an alternative anthem, HaEmunah (The Faith). But the song didn’t catch on and the rabbi refused to protest or show any disrespect if Hatikvah was played.

Labor Zionists also advanced a more socialist anthem, Chaim Nachman Bialik’s Techezakna (Strengthen Our Hands). And in the heady days after the Six Day War, some Knesset members suggested that Naomi Shemer’s Yerushalayim Shel Zahav (Jerusalem of Gold) get the nod for national anthem.

On November 10, 2004, the Knesset amended the the Flag, Coat of Arms and National Anthem Law to make it official once and for all: Hatikvah was enshrined as Israel’s national anthem. Among the lawmakers voting in favor was Druze MK Ayoub Kara, whose grandfather was an assistant to Sir Laurence Oliphant.

Related reading: The Miracle of the Resurrection of Hebrew

Objections to the ‘Jewish Soul’

It must be stated that not all Israeli minorities object to Hatikvah. But the ones who balk at it fall into two categories.

- Those who treat the song, like their citizenship, with respect, even though as Arabs, they understandably don’t identify with Israel’s Jewish characteristics.

- Those who anyway have no respect for the concept of Jewish nationhood.

Those who respect the state but do not identify with the song follow in the footsteps of individuals like Raleb Majadele, the first Arab Israeli cabinet minister. He refused to sing Hatikvah when it was played at state functions; instead, he simply stood silently. Majadele once explained why to Ynet:

Majadele told Ynet following interview that, “As a government minister, I swore allegiance to the laws of the State of Israel, and I intend to honor them.” Majadele noted that he expresses his respect to the national anthem by standing up whenever the song is being sung.

“To the best of my knowledge, the law does not require me to sing the anthem, but to honor it. I fail to understand how an enlightened, sane Jew allows himself to ask a Muslim person with a different language and culture, to sing an anthem that was written for Jews only,” he added.

Majadele wasn’t threatened by Israel’s Jewish identity as expressed in Hatikvah. And Israel wasn’t threatened by Majadele’s Arab identity as expressed by his silence. There’s room for both sides when it’s clear that the goal is coexistence, not conformity.

Related reading: What Does the Israeli Flag Really Represent?

Critics who can’t accept Jewish statehood require a different response.

The UN’s vote to create Israel was a decision to create an inherently Jewish state. It was a validation of Jewish nationhood, self-determination and aspirations, of which the lyrics of Hatikvah is just one manifestation. (Included in Israel’s creation and membership in the UN was a commitment by the Zionist leaders to treat minorities fairly.)

Other expressions of Israel as a Jewish state include:

Other expressions of Israel as a Jewish state include:

- The name of the state (Israel)

- The Israeli flag (Star of David)

- The Israeli seal (a menorah)

- The national language (Hebrew)

- The national calendar (Shabbat and Jewish holidays are statutory holidays)

A sizable percentage of the flags waving at the UN headquarters in New York feature Christian crosses and Islamic crescents. The national anthems sung at state affairs often reflect particular values that are meaningful for the majority, even if minorities feel little to no connection.

But to claim that Hatikvah is a racist song because its lyrics speak of a yearning soul in the Jewish heart defies belief. What of far more racist lyrics such as “Let an impure blood water our furrows” of the French La Marseillaise?

The Israel-bashers should consider how they would react if Hatikvah reflected the warrior emphasis of the Palestinian anthem, titled Fida’i (Fedayeen Warrior). It speaks of “the volcano of my vendetta” and its final words appear to embrace martyrdom:

The Israel-bashers should consider how they would react if Hatikvah reflected the warrior emphasis of the Palestinian anthem, titled Fida’i (Fedayeen Warrior). It speaks of “the volcano of my vendetta” and its final words appear to embrace martyrdom:

I will live as a warrior, I will remain a warrior,

I will die as a warrior – until my country returns.

Is it Israel’s place to tell the Palestinians what kind of anthem they should have?

The pioneers sitting around the campfire reading poetry under the stars more than a century ago had hopes and dreams of building a Jewish state.

The miracle is that the hopes and dreams of those halutzim expressed in Hatikvah are becoming a reality in Israel today.

Enjoyed reading this article? Follow the Israel In Focus page on Facebook to read more articles explaining Israel’s history, politics, and international affairs. Click here to learn more!

Featured image: vectors by freepik and vecteezy; Majdele via Wikimedia Commons; Palestinian flag CC BY-NC-SA AlHurriya;