For many observers of Middle Eastern politics, the relationship between Israel and Jordan is evidently marked by contradictions and fragility.

While economic ties between the two neighboring states continue to grow, Jordan is also one of the most vocal countries in its criticism of Israeli policy and members of the Jordanian parliament are known to use violent language in their condemnations of the Jewish state.

And while Israel and Jordan have both enjoyed stability on their borders for almost 30 years, there are occasional tensions that place a strain on the countries’ peace agreement.

To fully grasp the nature of the current relationship between the Jewish state and the Hashemite Kingdom (and why it seems strained), it is important to take a look at the century-long connection between these two countries and understand how this history has affected the present.

Here we will analyze the historical relationship between Israel and Jordan, focusing on the pre-state period, the years of conflict between 1948 and 1994, and the years of peace between 1994 and the present.

Join the fight for Israel’s fair coverage in the news

The Mandatory Period: 1920-1948

To fully understand the relationship between Israel and Jordan today, one has to go back to the early 1920s, before either Israel or Jordan existed as independent states.

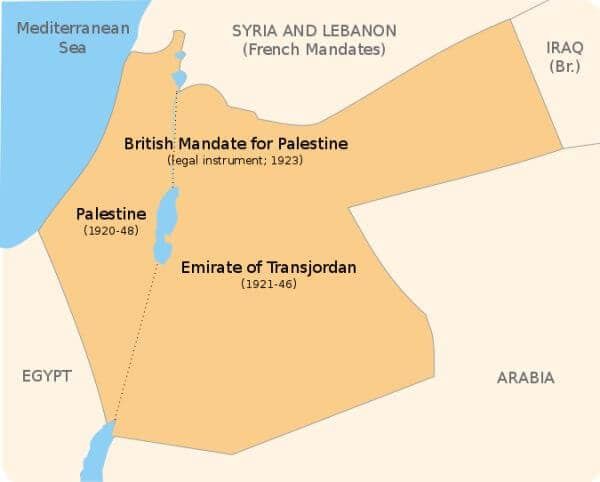

In the wake of the First World War, Britain and France carved up the former Middle Eastern territories of the Ottoman Empire, with each state gaining control and influence over their respective spheres.

In 1920, the San Remo Conference allocated the administration of the lands on both sides of the Jordan River to the British mandatory power.

However, eight months later, Britain excised the eastern bank of the Jordan River from the British mandate, effectively separating it into two separate entities.

In 1921, Britain designated the territory east of the Jordan River as the Emirate of Transjordan, under the leadership of Emir Abdullah bin Hussein. In 1923, Britain granted Transjordan semi-autonomy, with the local government having control over all the country’s affairs aside from financial, foreign and military matters (which remained in British hands).

In 1922, the League of Nations (a precursor of the United Nations) confirmed Britain’s mandatory rule over the territory west of the Jordan River and tasked the local administration with developing the territory as a future Jewish national home.

Related Reading: Balfour Declaration: ‘State’ or ‘Homeland’?

In 1946, Transjordan formally gained independence from Britain and became the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. While virtually independent of British control, its military, the Arab Legion, was still under the authority of British commanders.

At the same time, there was increasing restlessness in the British Mandate of Palestine as the colonial administration continued to rule with a heavy fist and stymie the creation of an independent Jewish state.

In November 1947, as the struggle for a Jewish state came to a head, the Jewish Agency sent Golda Meir (the future prime minister of Israel) to secretly meet with King Abdullah along the border and evaluate the Jordanian monarch’s intentions regarding the future Jewish state.

During the 50-minute conversation, Abdullah made clear that he would not stand in the way of the establishment of a Jewish state as long as Jordan gained control of part of the territory on the western bank of the Jordan, extending as far as the central cities of Lod and Ramle.

Abdullah also clarified that Jordan would not militarily engage with the Jewish state and would not allow the Iraqi military to pass through its territory on the way to fighting the Jewish state.

Twelve days after this meeting, the UN General Assembly voted for partition, effectively parceling the British Mandate of Palestine into a Jewish and Arab state.

Related Reading: In Focus: How The UN Partition Plan Led to Israel’s Birth

In early May 1948, the Haganah learned that, under pressure from both Palestinian Arabs and neighboring Arab states and also intrigued by the idea of gaining more territory, King Abdullah was reconsidering his intentions toward the burgeoning Jewish state. Once again, Golda Meir was sent to secretly meet with Abdullah (this time in Amman).

At this second meeting, the Jordanian ruler tried to convince the Jewish Agency to hold off on declaring statehood. Abdullah also proposed that Jordan would take over the territory of the British Mandate and grant the Jewish population autonomy. After one year, Jordan would annex the territory and grant the Jews representation in the Jordanian parliament.

Four days after this meeting, David Ben Gurion declared independence and the State of Israel was born.

Hours later, Jordanian military units rolled across the Jordan River and, along with neighboring Arab states, sought to put an end to the nascent Jewish state.

Years of Conflict: 1948-1994

In April 1949, following the conclusion of the Israeli War of Independence, Israel and Jordan signed an armistice agreement that left the Hashemite Kingdom in control of the areas known today as the West Bank and eastern Jerusalem. With its gaining of these territories, Jordan also attained control over half-a-million Palestinian Arabs, effectively doubling its population.

In 1950, Jordan formally annexed these territories, a move that was only recognized by Britain and Pakistan.

In 1951, on a visit to the Temple Mount compound in the Old City of Jerusalem, King Abdullah was assassinated by a Palestinian who was angered by the Jordanian leader’s seeming opposition to Palestinian nationalism.

Two years later, Abdullah’s grandson Hussein was crowned as ruler of the Hashemite Kingdom.

During the years of Jordanian control of the West Bank and eastern Jerusalem, Jews were forbidden from visiting Judaism’s holiest sites in the region.

In addition, during this period, Jordan allowed fedayeen (Palestinian fighters) to attack Israel from its territory. This often led to bloody Israeli reprisals over the border.

Related Reading: Before ‘Palestine’: Exploring the Unbroken Jewish Connection to Temple Mount

In 1965, Palestinian fighters from both Fatah and the PLO began to increase attacks against Israel from Jordan, with the support of Egypt and Syria. As the raids intensified, Jordan opened secret talks with Israel to discuss the threat that these Palestinian factions posed to both Jordanian stability and Israeli security.

After a particularly deadly Israeli reprisal attack within Jordanian territory in 1966, Jordan blocked the passage of Palestinian fighters from Syria into its territory and subsequently cut ties with Syria.

However, in 1967, as Egypt and Syria geared up for a conflict with Israel, Jordan resumed ties with Syria and entered into a security pact with both countries. One of the factors that may have contributed to this about-face was the Jordanian fear of continued Egyptian and Syrian support for Palestinian nationalists intent on overthrowing the Jordanian government.

In June 1967, as Israel faced off against the Egyptian and Syrian militaries in the Six-Day War, it tried to dissuade Jordan from entering the war. However, under the assumption that Israel was losing the war, King Hussein initiated hostilities against the Jewish state.

At the end of the war, Israel had pushed Jordanian forces across the Jordan River and gained control over both the West Bank and eastern Jerusalem.

After the war, Israel and Jordan continued to secretly communicate with one another and discussed cooperation in the face of growing Palestinian militancy (as symbolized by the PLO, Fatah and other Palestinian factions).

As a result of these secret talks, in 1971, Israel allowed Jordanian farmers to enter the Jordan Valley in order to work the land.

As the PLO continued to gain power in the early 1970s, the Palestinian group began to act as a state within a state, disregarding Jordanian law and authority.

Following the Dawson’s Field incident, when Palestinian terrorists hijacked five international flights and brazenly held foreign nationals hostage at a Jordanian airfield, the Jordanian army responded by ousting the PLO from the Hashemite Kingdom.

During the ensuing violence, which has been termed “Black September,” Syria sent 250 tanks into northern Jordan in order to support the Palestinian fedayeen. Jordan was able to repel the Syrian invasion and, during the retreat, Israeli planes overflew the Syrian troops as a way of showing support for the Hashemite Kingdom.

Ultimately, in 1971, the PLO was evicted from Jordan and moved to Lebanon.

Unlike the 1948 and 1967 wars, Jordan did not directly engage with Israel during the 1973 Yom Kippur War. Aside from a symbolic gesture of sending tanks to support Syria in the Golan Heights, Jordan stayed out of the Egyptian-Syrian surprise attack on the Jewish state.

Related Reading: PLO Still Lying About Arafat’s Legacy

Talks between Israel and Jordan continued after the Yom Kippur War but stalled in the late 1970s, with the rise of the Israeli government headed by Menachem Begin and the signing of the Camp David Accords between Israel and Egypt in 1978 (which advocated the granting of political autonomy to the Palestinians of the West Bank).

In the early 1980s, King Hussein and Yasser Arafat (the head of the PLO) reached a certain rapprochement but, frustrated by Arafat’s continued use of terrorism and failure to publicly recognize Israel, relations between them soured. In 1986, King Hussein announced that he would be responsible for the welfare of the Palestinians in the West Bank (to which Jordan still claimed a connection).

Around the same time, negotiations between Israel and Jordan began to intensify and, in 1987, Israeli Foreign Minister Shimon Peres forged an agreement with King Hussein in London.

According to this agreement, the five permanent member states of the UN Security Council would host peace talks about the future of the West Bank attended by Israel and a Jordanian-Palestinian delegation (that would not include the PLO).

Ultimately, this agreement was not approved by Israeli prime minister Yitzhak Shamir, due to internal political disagreements and his preference to only negotiate with the Jordanians, not Palestinians.

Nevertheless, this agreement laid the groundwork for the 1991 Madrid conference, which was attended by Israel (led by Shamir), Jordan, the Palestinians and other Arab countries.

Related Reading: Before the ‘Deal of the Century’: How Previous Israeli-Palestinian Peace Plans Failed

At the end of 1987, the First Intifada broke out, with Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza rioting and using violence against both Israeli soldiers and civilians.

In response, King Hussein tried to curry favor with the leaders of the Intifada but was rebuffed in favor of Yasser Arafat and his PLO.

In 1988, the Arab League effectively acknowledged the PLO as the sole representative of the Palestinian people. A few months later, the PLO declared the independence of a conceptual Palestinian state, which was immediately recognized by the Hashemite Kingdom.

Following the First Intifada and the aforementioned Madrid peace conference, Israel and Jordan signed a Common Agenda in 1993. This led to the Washington Declaration of July 1994 (which put an end to the official state of hostilities between the two countries) and ultimately the Israel-Jordan peace agreement, which was signed on October 26, 1994.

Related Reading: Palestinian Uprising: The First Intifada

Years of Peace: 1994 to the Present

A month after the signing of the peace agreement, Israel and Jordan established full diplomatic relations and exchanged ambassadors.

Along with a cessation of hostilities and the opening of official diplomatic relations, the peace agreement also recognized Jordan as the official custodian of Christian and Muslim holy sites in Jerusalem (including the Al-Aqsa Mosque).

Another one of the key elements of the peace agreement between Israel and Jordan was economic cooperation. In fact, the economic factor was so important that almost half of the agreement’s 30 articles dealt with economic matters.

The economic projects that Israel and Jordan cooperated on following the peace agreement include Israel’s providing 40-45 million cubic meters of water to Jordan every year, Israel’s providing natural gas to Jordan at a reduced rate, the granting of daily permits to two thousand Jordanians to work in the southern Israeli city of Eilat, the opening of the Haifa port to Israeli trade, the now-defunct Qualified Industrial Zone (which allowed for tariff-free Jordanian and Israeli exports to the United States), the use of Amman airport by Israeli tourists and cooperative projects between Israeli and Jordanian farmers.

In the security sphere, Jordan maintains stability on Israel’s eastern border and serves as a buffer for Israel from the threat of terrorist or other non-state actors. During Jordan’s fight against ISIS in 2015, Israel gifted the Hashemite Kingdom with 16 Cobra helicopters to aid in its defenses.

Although the Israeli-Jordanian peace agreement has provided gains for both countries, there have been fissures in the past and present that threaten the stability that the agreement brings to the region.

Some of the past incidents that have threatened to undo the peace agreement were the 1997 killing of seven Israeli students by a Jordanian soldier at the Island of Peace, the 1997 attempted assassination of Hamas leader Khaled Mashal by the Mossad in Amman, and the 2017 killing of an assailant and bystander by an Israeli embassy security official in Amman.

The Island of Peace was an area that had been ceded to Jordan along the Israeli border as part of the peace agreement and farmed by Israelis under a 25-year renewable lease. During the attack, a Jordanian soldier killed seven Israeli schoolgirls from the city of Beit Shemesh (aged 13 to 14) and wounded six more before being overpowered.

In each instance, the peace agreement could have been abrogated but gestures on the part of both countries helped cool the subsequent tensions.

In the Island of Peace incident, King Hussein visited the mourning families at their homes and visited wounded students at the hospital.

In the Khaled Mashal incident, Israel provided the antidote to Jordanian doctors and also released a number of Jordanian and Palestinian prisoners. In the embassy incident, Israel promised to remove metal detectors from the Temple Mount (that had been installed in order to curb violence at the holy site) as a means of assuaging the seething Jordanian response.

Aside from these specific incidents, other times that the fragility of the Israel-Jordan peace was exposed were the Second Intifada (when Jordan recalled its ambassador from Israel), tensions on the Temple Mount in 2014 (when Jordan recalled its ambassador for a few months) and the 2019 cessation of the “special regime” in the Naharayim (Island of Peace) and Arava areas by King Abdullah II (who succeeded his father, King Hussein, in 1999).

The special regime was a means by which Israelis were allowed to continue farming their land, even though it had been turned over to the Jordanians in 1994. After 25 years, the Jordanians refused to renew it and the Israeli farmers lost access to their lands.

Today, November 10th 2019, the two annexes to the peace treaty between Israel and Jordan, that established the special regimes in Naharayim/Bakura and Tzofar/Al Ghamr will expire and Jordanian law will apply in full.

Israel regrets Jordan's decision to terminate the annexes. >>> pic.twitter.com/zHlmJfCliH

— Israel Foreign Ministry (@IsraelMFA) November 10, 2019

One last fault line is the continued refuge granted to Ahlam Tamimi by the Hashemite Kingdom.

In August 2001, Tamimi took part in the heinous suicide bombing of the Sbarro restaurant in downtown Jerusalem. Aside from scoping out the location, which she chose as a ‘suitable’ location for a terror attack due to its popularity, Tamimi was also responsible for guiding the suicide bomber to the restaurant during the tail-end of the lunch-hour rush.

Once Tamimi left the scene, the terrorist detonated the 5 kg – 10 kg bomb that was embedded with nails, bolts and screws for maximum damage. 15 civilians between the ages of 2 to 60 (including five members of a single family) were killed in the attack and 122 were injured. One of those injured, US national Chana Nachenberg, is still hospitalized in a vegetative state.

Following the attack, Tamimi was sentenced to 15 life terms in Israeli prison but was subsequently released in 2011 as part of a prisoner swap between Israel and Hamas. Following her release, Tamimi was deported to her native Jordan.

Since two of the victims of the Sbarro attack were American nationals, Malka Roth (aged 15) and Shoshana Yehudit Greenbaum (aged 31), the FBI placed Tamimi on their most-wanted list and the United States has sought her extradition from Jordan ever since.

Even though Jordan has an extradition treaty with the United States, the Hashemite Kingdom continues to refuse to release Tamimi to the Americans.

While in Jordan, Tamimi hosted a program for Hamas TV and has become something of a local celebrity.

Ahlam Tamimi has never renounced her former activities, describing the attack as a “crown on my head” and saying that if she went back in time, she would do it all over again.

Nevertheless, despite these fault lines, Israel and Jordan’s relationship continues to grow:

In 2020, Israeli and Jordanian authorities expanded access to each country’s airspace for commercial flights.

In 2021, with the assistance of the United Arab Emirates, Israel and Jordan signed their largest-ever cooperation agreement.

In late 2022, both countries signed a letter of intent to cooperate on preserving the Jordan River.

Related Reading: Jordanian King Abdullah’s Role in Jerusalem: Mediator or Menace?

It is clear that Israel and Jordan have had a complex relationship for over 70 years.

While they were in an official state of war for almost 50 years, both countries maintained communication for almost that entire time and covertly cooperated on shared interests that benefited both states.

Now that Israel and Jordan enjoy peaceful relations and are continuing to grow and cooperate together, fault lines in the relationship continue to be exposed and threaten to undo all that has been accomplished over the past 30 years.

Though it may seem contradictory that Israel and Jordan had “friendly” relations before 1994 and now seem to exhibit hostile attitudes following the signing of the peace agreement, it can be surmised that both sets of relations extend from the same source.

Jordan occupies a tenuous position in the Middle East. A creation of the British Empire, the Hashemite Kingdom is one of the few Middle Eastern countries to never experience the overthrow of its royal family or have suffered coups throughout its century-long history.

Unlike states such as Syria or Iraq, Jordan also never came under the rule of socialist or pan-Arabist governments.

Thus, throughout the Cold War, Jordan’s positive relationship with the West and complicated relationship with the Palestinian Arabs made it a focal point of hostility from surrounding Arab nations and was seemingly always under the threat of attack from one of its neighbors. Therefore, while officially being in a state of war with Israel, Jordan relied on the Jewish state to help surreptitiously maintain its stability in the region.

Related Reading: AFP Deems Israelis Irrelevant for Peace With Jordan

Now that Israel and Jordan officially share peaceful relations, the Hashemite Kingdom still seems to find itself in the position of having to prove itself within the Middle East and the wider Arab world.

Therefore, while it might seem odd that one of Israel’s few Middle Eastern allies can be so publicly hostile towards it, this is a symptom of the current state of affairs and may not reflect the Hashemite Kingdom’s true feelings towards the Jewish state.

As one Israeli official noted in April 2022, “Jordan plays a double game with Israel, and is harsher in public than in private.”

Liked this article? Follow HonestReporting on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and TikTok to see even more posts and videos debunking news bias and smears, as well as other content explaining what’s really going on in Israel and the region.

Photo Credit: U.S. Embassy Jerusalem via Flickr