Part four of an eight-part series explaining The 8 Categories of Media Bias.

Violation #4

Lack of Context

Context describes the conditions in which something happens. Without a frame of reference for readers, journalists can dramatically distort the true picture.

For a newcomer to a contentious issue, context-free news is like walking into a cinema halfway through the movie and trying to make sense of a complicated plot. Context is the bridge that leads us from raw facts to deeper understanding.

That’s why journalists are taught to assume that their typical reader is learning about the topic at hand for the first time. Brief background lines, such as “the Temple Mount is revered by Muslims as the Noble Sanctuary and by Jews as the Temple Mount where two temples once stood,” or, “Israel first blockaded the strip in 2007 after Hamas violently overthrew the Palestinian Authority” are helpful, but in a limited way.

So why does basic background information — the history of a controversy, a who’s who of the key players, a glossary of commonly-used-but-barely-understood words, a geographic sense of place, overviews of political, ideological or religious divides, for example — get short shrift? Are major news outlets incapable of taking a step back from a story to educate readers of the bigger picture? Journalism professor Jay Rosen raises some important points out about context:

- The news industry rewards breaking news, not making it comprehensible.

- No metrics measure whether readers understood a report.

- Journalists get immersed in their beats and can forget what it’s like to be new to a issue.

And former McClatchy News executive Howard Weaver commented on Rosen’s post:

“Incrementalism in reporting — one or two new facts atop four paragraphs of old B-matter — don’t keep readers well informed. In fact, they may hurt; after while, we give up on chasing every incremental update. When we do tune in, what we get is a brief glimpse of parts of stories.”

Watch the Jerusalem Post’s Steve Linde and Gil Hoffman, The Algemeiner’s Ruthie Blum, and Dan Diker of the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs discuss missing context with HonestReporting.

Since this was first published, new examples have been added.

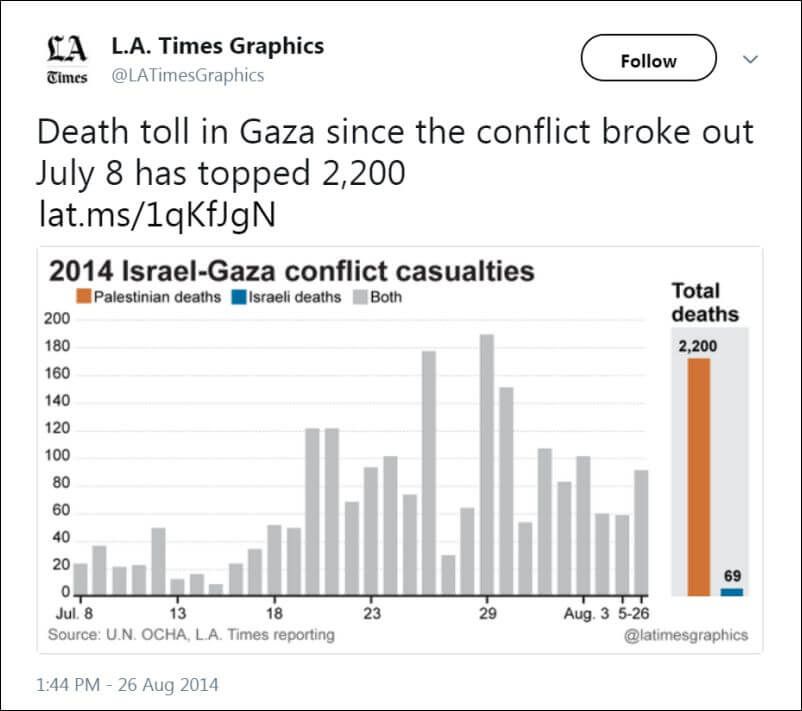

EXAMPLE: Infographics are a quick way of delivering information to readers on social media. But as “stand-alone” content that isn’t viewed with any accompanying article, there’s no way to adequately explain the nature of the numbers. This was painfully evident during the 2014 Gaza war, when papers like the New York Times, Los Angeles Times and others tweeted photos, infographics, and before/after satellite images of Gaza’s destruction.

Without understanding how pervasively Hamas embedded itself among Gaza’s civilian population, the death toll by itself became a prejudicial “moral barometer.” This Los Angeles Times infographic illustrates the point.

EXAMPLE: It’s a known fact that most people skim the paper’s headlines, only reading a limited number of articles. If everything a person knows about an incident is learned from headlines, that gives headline writers and copy editors more influence than the most careful journalist.

In a July, 2015 incident, Palestinians stoned a car carrying several IDF officers. The officers fired warning shots, the Palestinians continued throwing rocks, and the soldier fired back, killing one. Headlines from AFP, the Irish Times and New York Times, all failed on context.

For contrast, see how Reuters handled the headline:

EXAMPLE: Palestinian activists often post photos online without indicating the circumstances of what was photographed. One photo, dating back to 2001, is an important case study because A) of its overwhelmingly emotional nature, B) its world-wide distribution, C) the existence of a second photo providing context, and D) what one diplomat did with the image several years later.

On April 6, 2001, Evelyn Hockstein, of Reuters, photographed a Palestinian child being arrested by Israeli police. The look of fear on the kid’s face — along with his wet pants — made for a powerful image conveying the message that Israeli police are Palestinian child-snatchers. The image was subsequently used by Palestinian activists to demonize Israel.

What was the context of the photo?

The child was detained for throwing stones at police during a clash on Jerusalem’s Temple Mount. Another Reuters photographer, Natalie Behring, caught the same kid on film rearing back to throw.

The story of Hockstein’s photo didn’t end there. In 2009, a Norwegian diplomat working in Saudi Arabia, Trine Lilleng, caused a furor during Operation Cast Lead when she emailed two photos equating Israeli soldiers with Nazis.

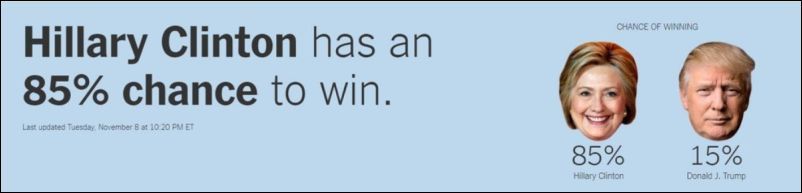

Other examples: Nikki Usher of The George Washington University’s School of Media and Public Affairs explained explained why the public was misled by mass media’s infographics and interactive features leading up to the 2016 presidential elections. It was a matter of context, not just faulty numbers.

Visualizing data as if it represents certainty is a serious problem. People consume information more quickly and effectively if it is visualized, but poor presentation and lack of context can lead to misinformation . . .

You’re going to see more and more of this. It’s addicting to users, perfect for Internet news consumption and beneficial to news organizations’ bottom lines. But it can also be dangerously unrepresentative of the actual complexity of the world around us.

Other examples: A New York Times story on blaming the West for problems absorbing Syrian refugees without acknowledging the role of Bashar Assad or Islamic State in creating the crisis. Then there are maps generated by individuals — perhaps even bots — which are shared on social media in order to spread misinformation.

Click to learn more about each individual category.

The 8 Violations of Media Objectivity

- Misleading definitions: Prejudicing readers through language.

- Imbalanced reporting: Distorting news through disproportionate coverage.

- Opinions disguised as news: Inappropriately injecting opinion or interpretation into coverage.

- Lack of context: Withholding a frame of reference for readers.

- Selective omission: Reporting certain events over others, or withholding key details.

- Using true facts to draw false conclusions: Infecting news with flawed logic.

- Distortion of facts: Getting the facts wrong.

- Lack of transparency: Failing to be open and accountable to readers.

See also the introduction to this series and some final thoughts and acknowledgements, wrapping the concepts together and raising awareness for news literacy.

“Red Lines: The Eight Categories of Media Bias,” is available on Amazon for purchase as an e-book.

Before you comment on this article, please remind yourself of our Comments Policy. Any comments deemed to be in breach of the policy will be removed at the editor’s discretion.