The Arab states attempted to destroy Israel before its very foundation by inciting their people to attack Jews. They tried to destroy Israel when they rejected the UN partition plan in 1947 and attacked Israel in the immediate aftermath of its independence in 1948. They tried to destroy Israel via terror attacks through the 1950s and 60s, and by closing off the Suez Canal in 1956. They tried to destroy Israel via a military assault from all sides in 1967. After failing to destroy Israel in all those attempts, and rejecting Israel’s overtures for peace in return for the land it took control of in the Six Day War, the Arabs came very close to achieving their goal in October 1973 in what became known as the Yom Kippur War.

Egyptian president Nasser passed away in September 1970 and his successor, Anwar Sadat, who explored options for a long-term peace agreement with Israel, was under pressure from the Egyptian street to restore Egypt’s honor from its defeat in the Six Day War.

In addition, the Egyptian economy was in a shambles, but Sadat knew that the deep reforms that he felt were needed would be deeply unpopular among parts of the population. A military victory would give him the popularity he needed to make changes.

Towards the end of 1972, Egypt began to build up its armed forces. It obtained MiG-21 fighter jets and advanced anti-tank guided missiles from the Soviet Union. In addition, generals who failed in 1967 were replaced with more competent officers and the army focused on improving its military tactics based on the practices of the Soviet military. Sadat declared that he was prepared to “sacrifice one million soldiers” in order to regain the territory which Egypt lost in 1967.

Sadat worked hard to gain backing from other countries for the Egyptian effort to recapture the Sinai and by the Fall of 1973, he claimed to have more than 100 states supporting this initiative – mostly from the Arab League and African countries. He also reached out to European countries and aside from the massive military and diplomatic support of the Soviet Union, he gained the support of the United Kingdom and France in the UN Security Council.

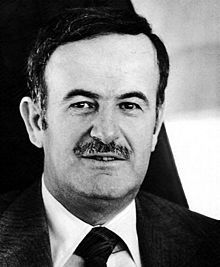

Syrian president Hafez al-Assad also initiated a massive military buildup with a plan to reconquer the Golan Heights. He also had dreams of establishing Syria as the most dominant military among the Arab countries. King Hussein of Jordan was reluctant to engage in a new war. He feared the possibility of losing even more territory than the West Bank which he lost in 1967. He was also upset with Sadat’s promise to Yasser Arafat of the PLO that he would be given control over the West Bank once Israel was defeated. King Hussein viewed the West Bank as part of Jordan and wanted to see it restored to his control.

Furthermore, in 1970, a near civil war broke out between Jordan and the PLO leadership during which the PLO was expelled from Jordan. Syria sided with the PLO and even helped it militarily, so Jordan did not feel comfortable joining the Egyptian-Syrian alliance. Iraq refused to join in on an attack because of its strained relations with Iraq, and Lebanon did not want to get involved because its army was small and unstable.

Sadat was set on war. His secret planning began in 1971 – keeping even the higher-level commanders out of the planning. The plan to attack Israel in concert with Syria was code-named Operation Badr after the Battle of Badr, in which Muslims, led by Muhammad, defeated the Quraish tribe of Mecca. In October 1972, Sadat told his Supreme Council of the Armed Forces that he intended to go to war with Israel.

Sadat publicly threatened war with Israel in a Newsweek interview in April 1973. Several times during that year, the Arab armies conducted large-scale exercises and each time Israel went on the highest alert levels for a few days. But commanders were not told of the actual war plans until less than a week before the attack and the Egyptian soldiers only learned about it a few hours beforehand.

On the Israeli side, there were plenty of warning signs that were ignored. On September 25, Jordan’s King Hussein secretly visited Israel to warn Prime Minister Golda Meir that the Syrians were going to attack Israel and that Egypt would join in. This was one of eleven warnings about war that Israel received from legitimate sources.

In October, IDF intelligence saw Egyptian military movement near the Suez Canal but dismissed it as mere training exercises. Israel also saw Syrian troops moving towards the border alongside a call-up of reserves and the cancellation of all military leave. But Israel’s intelligence leadership did not see all of this as a threat and did not listen to any of the warnings. They assessed correctly that Syria would not attack alone and would only do so in consonance with Egypt. They assessed incorrectly that Egypt was not going to attack.

Former President Nasser’s son-in-law, Ashraf Marwan, was a senior Mossad agent and told Israel that Egypt would not attack until the Soviet Union provided it with more MiG23 fighter jets and Scud missiles to fire at Israeli cities. Since the fighters had not yet arrived, and Egypt’s soldiers did not have enough time for the Scud training, Israel incorrectly assumed that Egypt was not ready to attack. Israel did send some reinforcement to the Golan Heights which proved to be a critical move.

On the day before the war, General Ariel Sharon, a future prime minister, saw intelligence information which showed a much larger concentration of Egyptian soldiers along the Suez Canal than would be used for training, along with equipment to be used for crossing the canal. He was certain that war was imminent and passed this information to his superiors.

Israeli intelligence saw Soviet advisers and their families leaving Egypt and Syria, Egyptian and Syrian tanks, infantry and missiles concentrated near the border at all-time highs, and transport planes filled with military equipment landing in the capital cities of Cairo, Egypt and Damascus, Syria.

Marwan, the Israeli spy at the highest of levels in the Egyptian government continued to warn of imminent attack but his warnings never made it from the intelligence arm to the prime minister. On the night between October 5-6, the head of the Mossad, Zvi Zamir, met with Marwan who told him that a joint Syrian-Egyptian attack would take place at sunset the next evening. Israel’s high command called for a partial call-up of reserves in response.

On the morning of October 6, Israel’s leadership considered a preemptive strike similar to its blow against the Egyptian air force before Egypt attacked in June 1967. But after hearing all the different opinions, Prime Minster Meir decided not to attack. She explained that Israel would need American military assistance to survive an Egyptian-Syrian attack and she feared that if Israel would attack first, it would be blamed for starting the war and would not receive that assistance. The prime minister’s fear was not unfounded. US President Richard Nixon and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger continuously warned Meir not to initiate the war. On October 6 itself, Kissinger reiterated to Israel that it should not initiate a preemptive strike.

On Yom Kippur, the holiest day in the Jewish calendar, on which most Jews spend a large part of the day in synagogue, just six hours after Israel decided not to launch a preemptive strike, Egyptian and Syrian forces attacked Israel – crossing the 1967 ceasefire lines in the Sinai in the south and the Golan Heights in the north. Egypt attacked with 100,000 soldiers and 1,350 tanks. At the time of attack, Israel’s forces at the Canal numbered 450 soldiers and around 100 tanks. Israel’s lack of preparedness enabled the Egyptian army to move into the Sinai with relative ease. Syria also made great progress and took over a significant area of Israeli controlled territory in the Golan Heights.

Israel found itself in a dire situation prompting the US to send an airlift of military equipment. This was also done to counter the massive supplies which the Soviet Union was sending to Egypt. The combination of the US airlift and Israel mobilizing most of its reserve forces enabled Israel to repel the assault.

Israel then launched an offensive attack to push Syrian forces out of the Golan Heights, which led the IDF deep into Syrian territory. When the Israeli army was within reach of the outskirts of the Syrian capital of Damascus, Egyptian President Anwar Sadat, realizing that the failed Arab campaign would soon come to an end, ordered his forces to go on the attack. Israel not only fought off this Egyptian advance but pushed the Egyptian forces back to the point that the IDF crossed the Suez Canal into Egypt and began advancing towards Egyptian cities including Cairo. But that progress came to a halt when a UN-brokered and US-pressured ceasefire went into effect on October 25.

The Syrian and Egyptian borders were not the only fronts that Israel had to defend during the war. Palestinian militias fired Katyusha rockets and anti-tank missiles from Lebanon into Israeli cities near the Lebanon-Israel border. They managed to lightly injure some Israelis and there was damage to Israeli property. The Israeli leadership decided that they could not open another battlefront and chose not to send forces into southern Lebanon to clear out the source of the rocket fire.

(Egypt violated the ceasefire the very next morning and despite the agreement, fighting actually continued until mid-January 1974.)

Israel lost more than 2,500 soldiers in the war and around 8,000 were injured. 293 Israeli soldiers were taken captive. The Arab armies which were joined by Iraq, lost anywhere between 8,000 and 18,00 soldiers (Egypt and Syria never released official numbers) and between 18,000 and 35,000 wounded.

Israeli prisoners of war were tortured terribly by their Syrian and Egyptian captors. IDF soldiers were found dead, having been executed while blindfolded with their hands tied behind their backs. Some were decapitated with axes, and high numbers were tortured with electric shocks all over their bodies including their genitals, burned with lit cigarettes, and had their fingernails ripped out. Many were held in captivity long after the war ended.

Aside from the horrific losses on both sides, the war had significant implications for both sides. The mistake of not acting on the intelligence warnings before the war led to Prime Minister Meir and Defense Minister Moshe Dayan resigning. Israel also eventually created a National Security Council to improve the communication and the coordination between the security/intelligence apparatus and the government.

But the war’s implications were far greater than that. The Arabs experienced conflicting emotions after the war, and both pushed them in the same direction. On the one hand the Arabs felt that while they failed in their goal of destroying Israel, they caused Israel significant damage and this restored their honor following their crushing defeat in the Six Day War, six years earlier. This gave them the ability to consider exploring peace with Israel “as equals.”

On the other hand, the Arabs saw Israel’s military might as it withstood their initial losses and then went on the offensive, reaching deep into their own countries. This fear of Israel’s strength also nudged them towards exploring peace. The Israeli side suffered a deep psychological blow as it suddenly realized that it was not invincible and had no guarantee of always defeating its Arab neighbors in war. This shifted Israel to a stronger determination of working towards peace.

The Soviet Union and the United States invited Israel, Egypt, Syria and Jordan to meet for a peace conference in Geneva in December 1973. The effort failed due to Syria’s refusal to attend. Through the efforts of the United States, Israel and Egypt signed the Sinai I agreement on January 18, 1974, in which Israel pulled back from some of its more advanced positions while still maintaining almost the entire Sinai.

The Sinai II agreement was signed on September 4, 1975, in which Israel withdrew from more land in the Sinai with UN forces moving in to patrol the area between Israel and Egypt. Israel still controlled more than two-thirds of the Sinai which was critical for it to hold as both sides explored a long-term agreement, a process which ultimately culminated with the 1979 peace agreement between Israel and Egypt.

The Syrian front was more complicated with military activity continuing between the two sides until May 31, 1974 when the US brokered a “disengagement agreement” in which Israel withdrew from Syria back to the Golan Heights, Syria agreed to release its prisoners of war in a prisoner exchange, and the UN established the UN Disengagement and Observer Force keeping the peace in a buffer zone created between the two countries.

The Yom Kippur War marked the last time that the Arab countries neighboring with Israel joined together militarily to try to destroy the Jewish state.