Every so often, readers ask us, “Can’t we sue the media for bias?”

People posing this question tend to make any or all of the following points:

- Apologies and corrections are a waste of time.

- Free speech also carries responsibility.

- The threat of costly damages should scare the news industry into better accountable.

No simple matter

First of all, Western free speech laws are very strong, meaning that a plaintiff would have to be able to demonstrate that the news coverage in almost any case was an outright lie. Period. Misleading coverage that has enough truth to it would not be actionable in a court of law. (Legal beagles are invited to hash out the finer points in the comments section.)

Second of all is the question of who has “standing” to sue? Standing refers to who has the right to sue because they were directly harmed. The vast majority of the problematic media coverage we see is biased against the state of Israel, not against specific people.

Join the fight for Israel’s fair coverage in the news

In any event, states don’t sue foreign journalists for three reasons:

1. Enforcement: Countries with free speech laws enforce defamation against individuals more strongly than defamation against organizations. That distinction makes it prohibitive for any country to theoretically sue a media service. In many jurisdictions, states are prohibited from suing over defamation at all.

2. Jurisdiction: Even if a country like Israel were to sue a foreign news outlet, would the lawsuit be filed in Israel, the home state of the news service, or perhaps the area where the corporate headquarters are? Much would depend on where the media outlet’s money is located and whose free speech rules would be most advantageous.

3. Other means: States have other ways at their disposal to fight problematic news. States can withhold or withdraw press credentials (like when Israel suspended, then restored credentials for Al Jazeera’s bureau chief). There are also potential diplomatic channels for political leaders to contact the highest level news executives.

Governments can also choose to boycott specific journalists. One example of this was in 2003, when Israel prohibited government officials from appearing on BBC shows (The BBC was not barred from press conferences.)

Boycotting a news service is a powerful card to play; in the news industry, access is everything. But such boycotts aren’t in either side’s best interests and therefore don’t last long. The relationship between the press corps and any government is a two-way street. Just as journalists need access, news-makers need exposure.

Related reading: Related reading: Is Antisemitism Legally Protected Free Speech?

Individuals suing the media

Let’s say some activists are looking for an individual with standing to sue a news service. They would need a clear-cut plaintiff who has A) suffered as a result of sloppy media coverage, and B) has the finances and fortitude to wage a lengthy legal battle whose outcome is by no means certain. Such lawsuits aren’t common in regards to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, but two come to mind.

One was filed by the late Ariel Sharon against Time. In 1983, the magazine falsely reported that Sharon, then minister of defense, had encouraged Lebanese Phalangists to massacre Palestinians living Beirut’s Sabra and Shatila refugee camps after the assassination of Lebanese president Bashir Gemayel.

Sharon and Time reached an out of court settlement in 1986 in which Time paid an undisclosed but reportedly “substantial” sum. Under the terms of the settlement, Time also admitted that the description of Sharon’s alleged conversations with Phalangists in Beirut was “erroneous.”

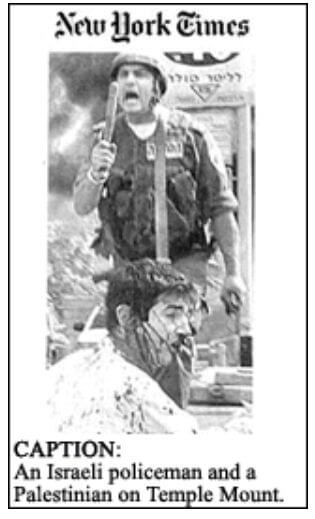

More recently was a lawsuit against Associated Press and the French paper, Libération over a September, 2000 photograph incorrectly describing US student Tuvia Grossman — who had been rescued from a Palestinian lynch mob — as a Palestinian.

More recently was a lawsuit against Associated Press and the French paper, Libération over a September, 2000 photograph incorrectly describing US student Tuvia Grossman — who had been rescued from a Palestinian lynch mob — as a Palestinian.

A Paris judge in 2002 ordered the two news services to pay Grossman 4,500 Euros in damages for misrepresenting him. (Read more about Grossman’s story and how it played into HonestReporting’s founding by seeing The Photo That Started It All.)

In one other instance, the mere threat of legal action was enough to make a difference.

In May, 2012, The Guardian wrote that Tel Aviv was Israel’s capital. When complaints to both The Guardian and the then UK’s Press Complaints Commission were rejected, HonestReporting threatened legal action. In the end, The Guardian backed down, making a retraction and revising its style guide.

Related reading: Boycotting Israel: Is It Free Speech?

Why apologies matter

An apology, according to Merriam Webster, is simply “an admission of error or discourtesy accompanied by an expression of regret.” For legal purposes, an apology is “a public plea for forgiveness to undo some damage” and may be accompanied by the publishing of correct information and perhaps a financial payment of one form or another.

Just as information, quotes, headlines, photos, videos, podcasts, etc. are “on the record,” so are the corrections. And in the internet age, anyone can get online and see, for example, what Natjonal Public Radio had to say about a map error or how the International Business Times handled a grossly inaccurate Temple Mount report (the story was removed from the web site).

Granted, corrections aren’t usually seen by only a fraction of the people who saw the original erroneous reporting. But a lack of transparency is a form of media bias by not being open and accountable.

Sometimes, legal action is both an appropriate and practical option. In the past, relevant parties, including HonestReporting, have gotten involved in such battles. However, the Western world generally accepts that freedom of speech is such a high priority that legal action for biased news is rendered impractical or impossible.

That’s why HonestReporting has developed advocacy skills for readers and relationships with journalists. Sometimes the best remedy for biased speech is more and better speech in return.

Daniel Pomerantz contributed to this post.

Featured image: vectors by Vecteezy;

Before you comment on this article, please note our Comments Policy. Any comments deemed to be in breach of the policy will be removed at the editor’s discretion.