“What did you do when the world went into lockdown in 2020?” That’s a question the answer to which many people will be retelling for years to come.

For many Palestinians, the answer was the same as for most other people: they stayed home, practiced some form of social distancing, and wore masks.

It’s been relatively quiet in Israel this week, which may explain why the Guardian’s new correspondent in Jerusalem, Bethan McKernan, has now dredged up a story of how one Palestinian man used his time during the lockdown to digitize an old music album, romanticizing it as the uncovering of a “treasure trove” that included long-forgotten music that animated Palestinian life during the 1980s.”

McKernan describes the music as being recorded at the time “when the first intifada (uprising) broke out.”

Join the fight for Israel’s fair coverage in the news

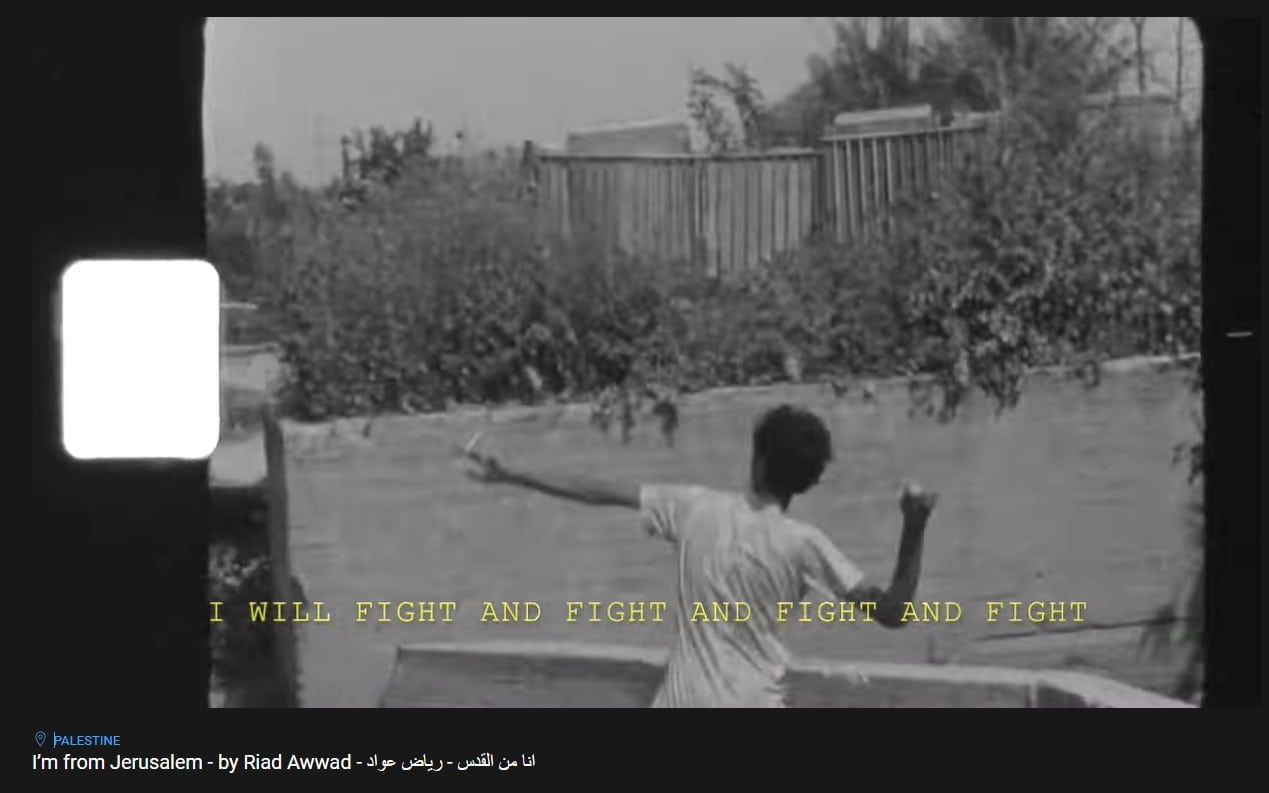

Notably, McKernan does not refer to the lyrics of the songs. One, “I’m from Jerusalem,” by Riad Awwad, includes the refrain “I will fight and fight and fight and fight,” and speaks of the places that the singer desires to fight: streets, factories, farms, alleyways.

Yet despite the video being embedded on the Guardian website, McKernan fails to note the lyrics in any way, meaning that readers of the print edition are left uninformed as to the precise words of the songs. Similarly, she does not describe how a youth throwing a rock against Israeli military infrastructure is depicted in the video. This needs to be stated clearly as fact.

Instead, McKernan describes how Israeli security forces “confiscated most of the 3,000 tapes… over fears the lyrics – some of which mention Molotov cocktails and throwing stones – would incite people to violence.”

McKernan depicts Israel as acting “over fears” that the song lyrics “would incite people to violence.” In doing so, she engages in a version of a practice routinely employed by journalists, that of citing Israeli concerns by using phrases such as “Israel says” or “the IDF said,” rather than stating these concerns as facts.

Here’s what the article misses out on altogether:

The Intifada wasn’t simply a “struggle for freedom,” to use McKernan’s words. If that were the case, then Israeli soldiers alone would have been the targets of Palestinian violence. But though media reports such as this tend to frame the First Intifada’s extreme violence as a form of “protest against the Israeli occupation,” as if Palestinians engaged only with Israeli soldiers, the truth is that between 1987 and 1993, the number of Israeli civilians killed (175) was higher than the number of troops and security personnel killed (102).

Related Reading: Palestinian Uprising: The First Intifada

From the very beginning of the Intifada, Israeli citizens were considered legitimate targets and many were attacked as they drove or walked through predominantly Arab areas. Most were not seriously harmed, but media portrayals of the period almost invariably disproportionately focus on Palestinian youths armed with rocks and slingshots and not on their Israeli victims.

Notable terror organizations such as Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ) and Hamas were involved in the violence. PIJ masterminded several suicide attacks in Israel, including a suicide attack on a bus in 1989, when a terrorist killed 16 people after seizing the steering wheel of a bus and driving it off a steep cliff into a ravine in the region of Kiryat Ye’arim, located near Jerusalem.

In another PIJ attack at the height of the Intifada, a busload of Israeli tourists traveling not far from Cairo were ambushed by gunmen. Nine Israeli passengers and two Egyptians were killed in the carnage.

Over the course of six years, Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza regularly participated in violent demonstrations and launched attacks against Israeli soldiers and civilians alike.

According to the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF), tens of thousands of rock-throwing attacks took place during the first four years of the Intifada alone. There were also in excess of 3,600 assaults using Molotov cocktails, 100 hand grenade attacks and 600 incidents involving guns or explosives. Many thousands of Israelis — both soldiers and civilians — were injured.

In short, the Intifada posed a serious threat to Israel, and fears of violence weren’t just Israeli “fears” as McKernan depicts, much less over Molotov cocktails and throwing stones alone, as the lyrics of the songs reference explicitly.

This latest article by McKernan is entirely in keeping with a long list of such pieces, failing to hold the Palestinians to account for such violence, and essentially romanticizing their murderous “struggle.”

Most disconcerting, media accounts such as this fail to mention at all how the uprising was used by the Palestinian leadership as an excuse to conduct purges. As the uprising began to quiet down in early 1991, most of the deaths on the Palestinian side came from the Palestinian leadership executing anyone suspected of collaborating with the Israelis. These “collaborators” were found hacked to death with axes, clubbed, burned with acid, stabbed, and shot. From 1989-1992, 1,000 Palestinians were killed under this pretext.

Yet none of this is mentioned in The Guardian.

Why not?

Liked this article? Follow HonestReporting on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and TikTok to see even more posts and videos debunking news bias and smears, as well as other content explaining what’s really going on in Israel and the region. Get updates direct to your phone. Join our WhatsApp and Telegram channels!