“Historic Palestine” is a commonly-used term when discussing the Arab-Israeli conflict. The phrase suggests that a nation known as Palestine existed in the past, with the word “historic” giving the impression that this nation has deep roots in the region and thus has a natural claim to be revived in the form of a modern state called Palestine. By referring to the land thus without mentioning Jewish history, it also subtly suggests that a Jewish presence is foreign to the region.

This article discusses the origin and evolution of the usage of “Palestine” as a place name and how current notions of “Historic Palestine” are all based on a false understanding of the geographic and political history of the region.

Historic Palestine in today’s usage typically refers to the territory that now comprises Israel, the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. Here are several recent prominent examples of usage of the term:

- Saeb Erekat, chief negotiator for the Palestinian Authority, stated in an opinion piece published in the New York Times in May 2019 that the Palestinians recognized Israel on the “1967 border, equivalent to 78 percent of historic Palestine.”[i] Which “historic Palestine” was Erekat referring to and does Israel really comprise 78% of this “historic” territory?

- The Columbia Journalism Review published an article in January 2019 titled “Palestinian citizens of Israel struggle to tell their stories” in which the author claimed that “Historic Palestine under Ottoman and British control had a thriving Arabic press.”[ii] Was Palestine ever a territory under Ottoman control?

- A June 2019 article in The Washington Report on Middle East Affairs about Trump’s “Deal of the Century” for Middle East peace states that the deal could leave the “New Palestine” in charge of “about 12 percent of historic Palestine.”[iii] What land area was used to arrive at this figure?

- President Abbas noted the following in his address to the United Nations in November 2012: “The two-state solution, i.e. the State of Palestine coexisting alongside the State of Israel, represents the spirit and essence of the historic compromise embodied in the Oslo Declaration of Principles, the agreement signed 19 years ago between the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and the Government of Israel under the auspices of the United States of America on the White House Lawn, a compromise by which the Palestinian people accepted to establish their state on only 22% of the territory of historic Palestine for the sake of making peace.”[iv] Is this 22% number accurate?

Join the fight for Israel’s fair coverage in the news

Geographic History of the Holy Land

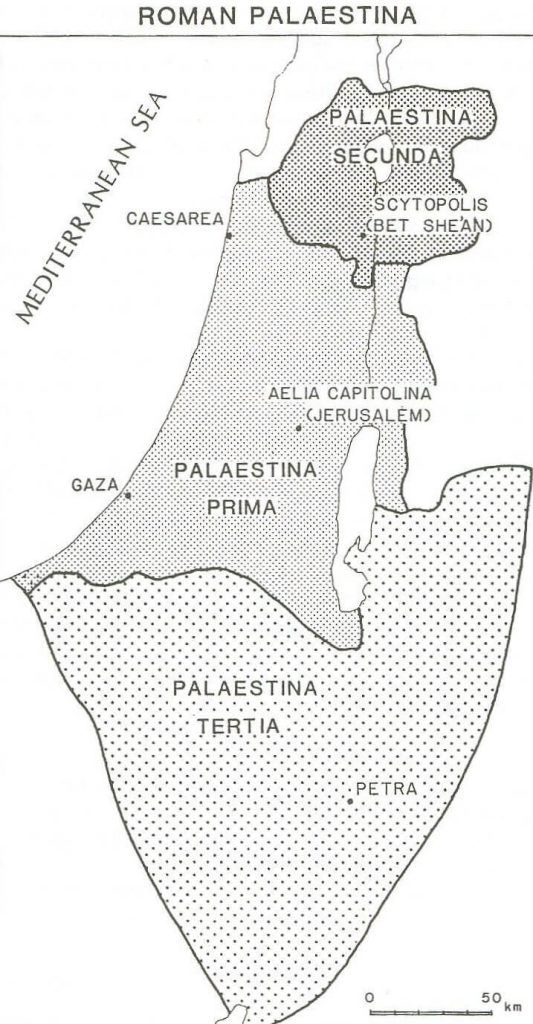

Palestine, or officially “Provincia Syria Palaestina,” was a name invented by the Romans in 135 CE as a replacement for “Judea,” in an effort to eliminate all expressions of Jewry in the region following the defeat of Bar Kohba in the Jewish rebellion against the Roman Empire. Similarly, Jerusalem was officially renamed Aelia Capitolina. In the fourth century, the province was split into three smaller units: Palaestina Prima, Palaestina Secunda and Palaestina Tertia, (see Map A). Note that the new provinces were organized horizontally and comprised areas on both sides of the Jordan River.

In the early seventh century Islam emerged in Arabia and Muslim armies began to conquer large portions of the Middle East, including the three “Palaestinas” in 640 CE. The Muslim conquerors roughly maintained the Roman-Byzantine divisions of the region: Palaestina Prima was renamed “Jund Filastin” (military district of Filastin), and Palaestina Secunda was renamed “Jund Al-Urdunn” after the Jordan River. Palaestina Tertia ceased to be a separate district and became part of the desert territory to the south. Jund Filastin and Jund Al-Urdunn comprised two out of five provinces (along with Jund Dimashk, Jund Hims, and Jund Kinnasrin) that formed a larger geographic region known in Arabic as “Esh-Sham” or “Bilad al-Sham.” Bilad al-Sham meant “land of the left hand,” as opposed to “Bilad al-Yaman” which meant “land of the right hand.” When one stood at Mecca or Medina and faced east, Bilad al-Sham was positioned on the left or to the north, while Bilad-al Yaman sat on the right or to the south. “Esh-Sham” also referred to the city of Damascus, and its broader meaning was the entire region that was ruled from Damascus. Esh-Sham later became associated with “Syria” and the concept of “Greater Syria,” further discussed below.

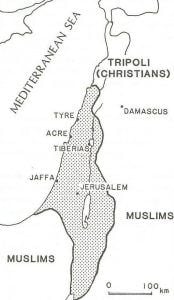

Esh-Sham and the Jund districts remained in place until the Christian Crusader conquest in 1099 CE. The newly formed Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem started as a small territory, then gradually expanded to comprise an area at its height ran from a point north of Beirut to the Sinai Desert and both sides of the Jordan River, as shown in Map B. The Christian rulers did not designate a province or district as Palestine. Over the next two centuries, a series of back-and-forth military actions between Muslims and Christians led to fluctuating borders, but by the end of the thirteenth century, the Crusaders were completely expelled by the Mamelukes. The Crusader period and the establishment of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem instilled a consciousness within the Christian world of the Holy Land as one geographical unit, and heightened religious associations with the region which would carry into the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

The Mamelukes remained in control for the next few centuries and implemented new geographical divisions, naming provinces according to their principal cities. For most of this period, the land on both sides of the Jordan River was divided into six districts, with capitals at Gaza, Hebron, Jerusalem, Ludd, Nablus and Qaqun (a town north of Jaffa). As in earlier Muslim empires, these districts were considered part of a larger Esh Sham/Bilad al-Sham territory whose center was at Damascus. The Mamelukes did not name any territory Palestine/Filastin, which by this time had little meaning other than as the former name of a province in the long extinct Christian Roman-Byzantine Empire.

In 1516, the Mamelukes were displaced by another Muslim empire, that of the Ottoman Turks originating from Asia Minor. The Turks implemented new geographical designations for their conquests, dividing the territory into administrative provinces known as Eyalets. Initially, most of the territory which today comprises Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Israel, the West Bank and the Gaza Strip (which can be designated as the “Modern Nations”) became incorporated into the single Eyalet of Sam, which generally conformed with the prior region known as “Esh Sham.” Once again, the Ottomans did not identify any territory as Palestine/Filastin, although Ottoman historians and scholars were certainly familiar with the history of the region and the old place name. Palestine had also become an irrelevant name to Jews, who preferred “Eretz Israel” (Land of Israel), and to the Arabs and Muslims, who continued to refer to Esh-Sham. Even among Christians, Palestine was a lost name for much of the Ottoman era, as they preferred calling the region the “Holy Land” or “Judea.”

Join the fight for Israel’s fair coverage in the news

The administrative boundaries and names of the Eyalets changed several times over the centuries, and in the early nineteenth century, the Eyalet of Sam was divided into three new Eyalets: Aleppo, Sidon and Damascus. The area usually associated with the Holy Land was mostly comprised of the Eyalets of Sidon and Damascus, so administration was handled out of today’s Lebanon and Syria. In 1864 the Ottomans enacted another administrative reorganization, which eliminated the old Eyalets in favor of new provinces called Vilayets, in turn divided into sub-districts called Sanjaks. Each Vilayet was governed by a Vali, or governor-general, and each Sanjak was governed by a Mutesarrif. The reorganization created a new Vilayet of Suriya, the Arabic form of Syria, which was essentially a union of the former Eyalets of Sidon and Damascus, with a Vali based in Damascus, which comprised most of the territory of the Modern Nations. The establishment of this province was the first time that the name “Syria” was officially used by the Ottomans to designate a territory.

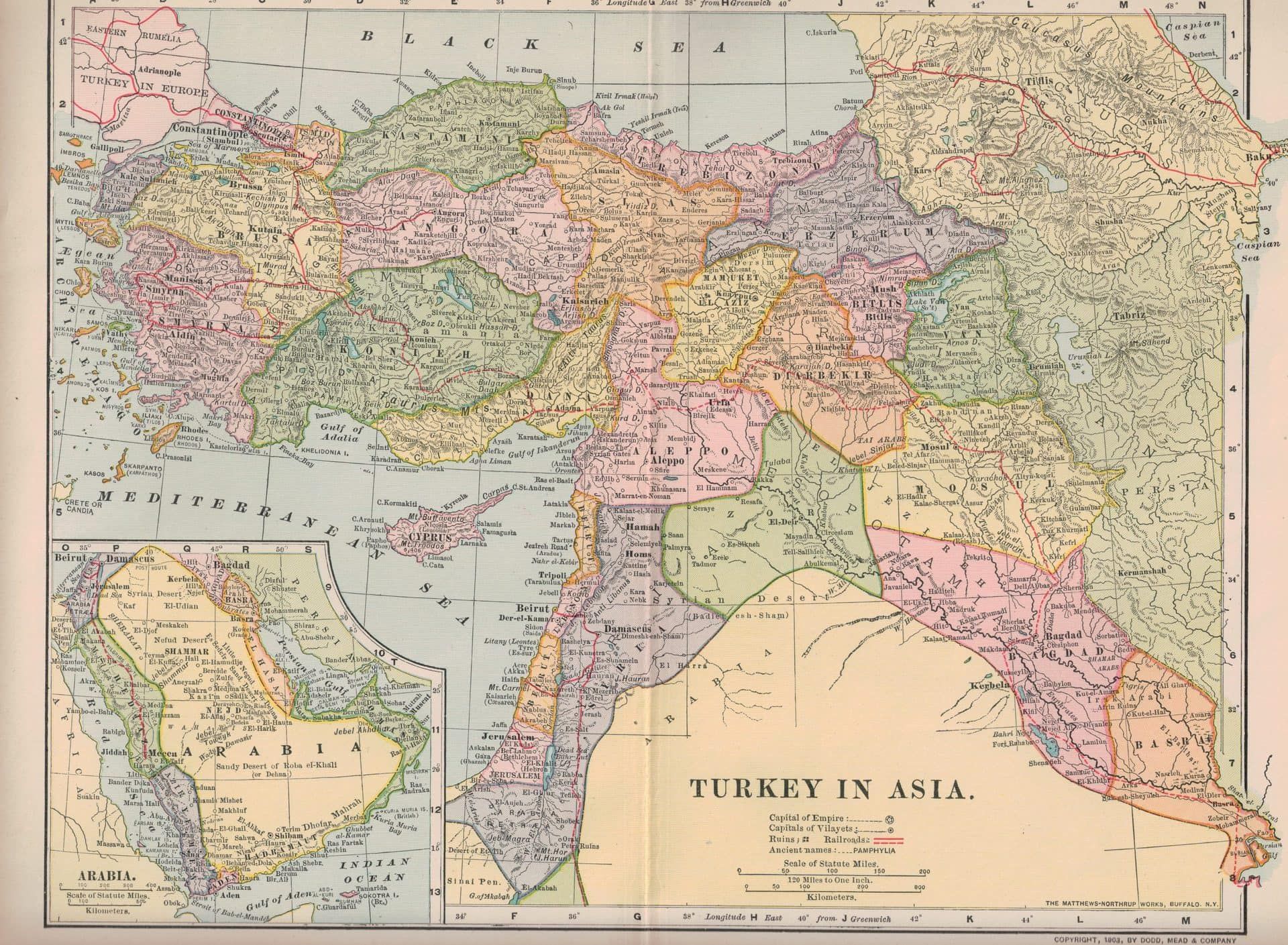

Less than a decade later, in 1873, the Ottomans enacted yet another administrative change to the districts by carving out a portion of the Vilayet of Suriya to create a province called the “Mutasarrifiya of Jerusalem.” A Mutasarrifiya (or Mutessariflik) was a province similar to a Vilayet, with a governor that reported directly to the Sultan. The Sultan created this province headquartered in Jerusalem that would report directly to him because of the growing importance of the holy city in world politics, mainly due to a growing European interest in the region. In 1888, the Vilayet of Suriya was further reduced with the creation of a new Vilayet of Beirut, which contained five Sanjaks: Latakia, Tripoli, Beirut, Acre and Nablus. This administrative regime, as shown in Map C, remained generally stable through World War I.[v] The purple area represents the reduced Vilayet of Syria, while the new Mutasarrifiya of Jerusalem is in pink. The new Vilayet of Beirut is north of the Mutasarrifiya of Jerusalem in orange. In this organization, areas normally associated as part of Palestine, such as Nablus, Haifa and Acre, were part of the Beirut province, which is not unusual because the Ottomans did not distinguish between areas in today’s northern Israel and southern Lebanon. The one commonality throughout the various administrative changes under Ottoman control is that Palestine as a place name never came into consideration, even as a smaller administrative territory like a Sanjak. By the time World War I broke out, “Palestine” as a location had been extinct for nearly a millennium, a vestige of ancient Roman rule.[vi]

Palestine: Maintaining an Ancient Name

Even though the Ottoman Turks, who controlled the region for centuries and maintained their own political boundaries that did not include the long extinct place name “Palestine,” and even though no one in the region would have considered themselves “Palestinian,” the term came back into use in the 1800s – but not by the Arab or Jewish inhabitants of the region or the ruling Ottomans, but by foreign Christians. Sometime during the European Renaissance, with its renewed interest in the classical world, Christian interest in the Roman name “Palaestina” reemerged, later strengthened by Napoleon’s foray to the Middle East in 1799. Although it had long ago been discarded by the Ottomans, Jews, Muslims, Arabs and even most Christians, the centuries-old name for the old Roman land of Jesus and the Bible became relevant again.[vii]

Related reading: What’s in a Name? The Origins of Judea, Philistia, Palestine and Israel

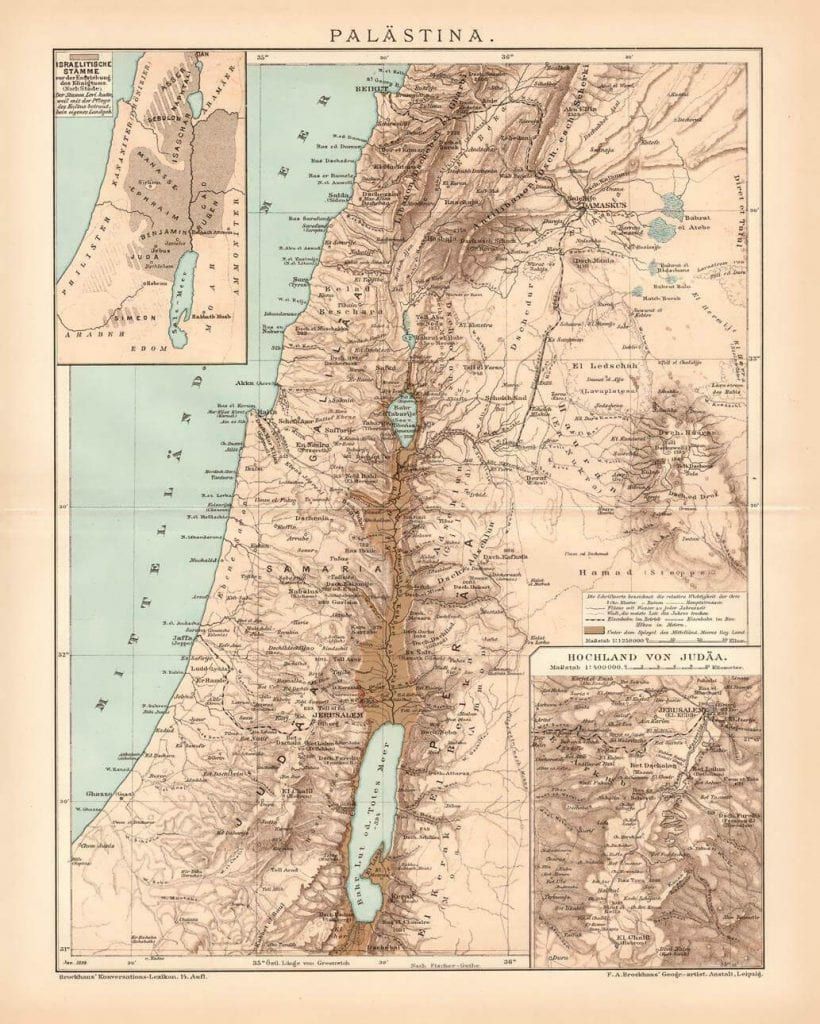

The first attempt to accurately map and delineate a distinct territory called “Palestine” is usually credited to Pierre Jacotin, a member of Napoleon’s entourage, published soon after the expedition. Many other maps were produced in the nineteenth century, but the highest quality version was published by the Palestine Exploration Fund in 1878. These maps had little in common with the actual political boundaries established by the Turkish authorities and were instead based on notions of a territory outlined in the Bible. As one scholar of nineteenth-century geography of the region explained: “…these mappers were perhaps more concerned with illustrating the book of Joshua than in helping future historians of the Ottoman Empire…”[viii] As might be expected, the maps also varied significantly, as cartographers were uncertain of how to map a territory based solely on verbal descriptions in ancient texts. One example is shown in Map D, published in Germany in 1892. It shows Palestine, as well as an insets of the ancient Tribes of Israel and the Judean highlands.[ix] The Encyclopedia Britannica of 1911 best described the ambiguity of this nebulous place called Palestine:

PALESTINE, a geographical name of rather loose application. Etymological strictness would require it to denote exclusively the narrow strip of coast-land once occupied by the Philistines, from whose name it is derived. It is, however, conventionally used as a name for the territory which, in the Old Testament, is claimed as the inheritance of the pre-exilic Hebrews; thus it may be said generally to denote the southern third of the province of Syria. Except in the west, where the country is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea, the limit of this territory cannot be laid down on the map as a definite line. The modern subdivisions under the jurisdiction of the Ottoman Empire are in no sense conterminous with those of antiquity, and hence do not afford a boundary by which Palestine can be separated exactly from the rest of Syria in the north, or from the Sinaitic and Arabian deserts in the south and east; nor are the records of ancient boundaries sufficiently full and definite to make possible the complete demarcation of the country…Taking as a guide the natural features most nearly corresponding to these outlying points, we may describe Palestine as the strip of land extending along the eastern shore of the Mediterranean Sea from the mouth of the Litany or Kasimiya River (33° 20′ N.) southward to the mouth of the Wadi Ghuzza; the latter joins the sea in 31° 28′ N., a short distance south of Gaza, and runs thence in a south-easterly direction so as to include on its northern side the site of Beersheba. Eastward there is no such definite border. The River Jordan, it is true, marks a line of delimitation between Western and Eastern Palestine; but it is practically impossible to say where the latter ends and the Arabian desert begins. Perhaps the line of the pilgrim road from Damascus to Mecca is the most convenient possible boundary.

As defined in this authoritative British-published encyclopedia, Palestine included parts of today’s southern Lebanon and territory east of the Jordan River, but mostly excluded the Negev Desert.

Join the fight for Israel’s fair coverage in the news

When you sign up for email updates from HonestReporting, you will receive

Sign up for our Newsletter:

Join the fight for Israel’s fair coverage in the news

Historic Palestine: An Anachronism

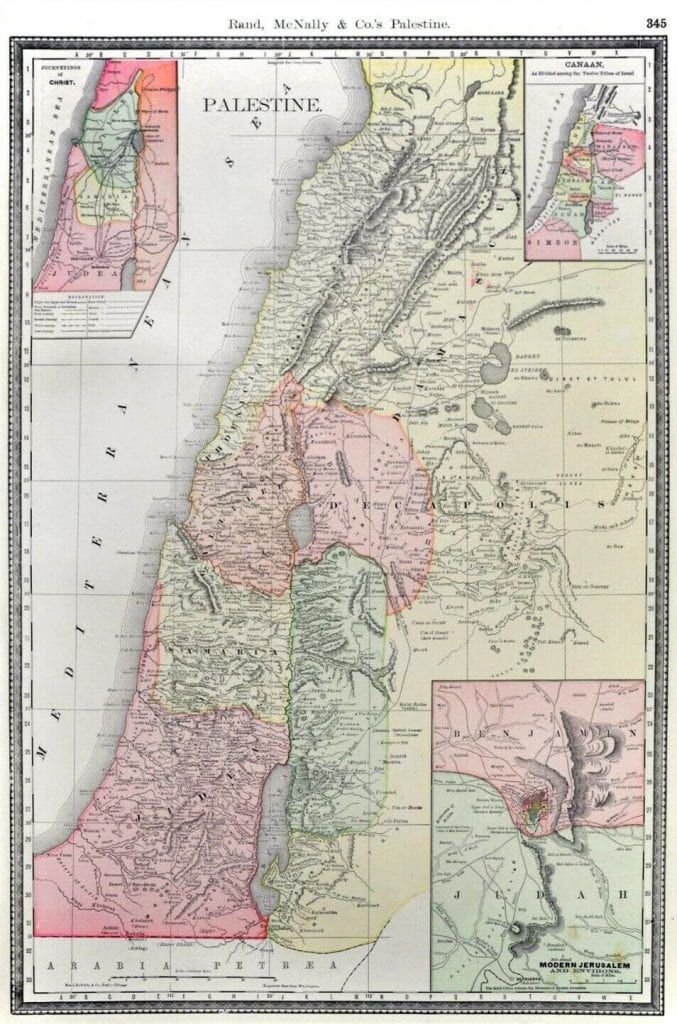

The actual political geography of the region was accurately represented in most world atlases, correctly included in maps of the Ottoman Empire or Turkey, or more specifically, “Turkey in Asia” (as shown previously in Map C) as opposed to “Turkey in Europe.” These maps correctly show the Ottoman subdivisions, with Palestine no where to be found, because it did not exist. Strangely, but conforming to the Biblical interest in the Holy Land by Christian Europe and America, these very same modern world atlases separately included a map of “Palestine” along with the map of Ottoman Turkey, as can be seen in this example from Rand, McNally’s “business atlas” published in 1892 (see Map E, similar to the German example seen in Map D).[x] This curious decision would be similar to a 2019 world atlas depicting, for example, a map of modern Iraq and then in another page displaying a map of ancient Sumer – with no other ancient map or extinct geography of any other country offered. Why did these contemporary atlas publishers provide a map of Palestine going back to the Roman era? Because of a belief that the land of Jesus was required reading, even in an atlas dedicated to depicting the modern world.

Many modern historians have adopted this anachronism sometimes describing or showing maps of Palestine as it supposedly appeared during the Ottoman era.[xi] However, all these depictions are flawed, since the Ottomans did not designate any territory as Palestine, or use the name in any official capacity.[xii] Unfortunately, it has become convention to superimpose today’s typical definition of “Historic Palestine” (i.e. the territory comprising today’s Israel, the West Bank and the Gaza Strip) over maps of the Ottoman Empire, thereby conveying the false impression that today’s definition is somehow based on Ottoman geography.

The British and French would later also ignore the Ottoman Vilayet system, instead carving up the region solely based on the strategic needs of the two powers. Remarkably, when the British negotiated with the French after World War I regarding the borders of the new Palestine Mandate, the initial British stance was based on the vague biblical designation of the Land of Israel as lying “from Dan to Beersheba” (I Samuel 24:2). Gideon Biger, a renowned scholar on the geography of the region, explains, “This biblical formula, brought forth by the Bible-knowing British, has quickly become the central formula in determining the future boundaries of Palestine.”[xiii]

Join the fight for Israel’s fair coverage in the news

These twentieth century European-created borders, which continue to be invoked in today’s discussion of the conflict, are somehow treated today as long-standing and sacred, while the Ottoman designations are a distant memory. Another key error in today’s usage of “Historic Palestine” is that the conventional definition excludes areas east of the Jordan River, even though throughout history, from the Roman-Byzantine era to nineteenth-century maps and the initial formation of the British Palestine Mandate, portions of today’s modern Jordan were always considered part of Palestine.

It’s All Really “Historic Syria”

While the terminology of the holy land is often focused on Palestine, to fully understand the geographic history of the region it is important to understand the usage and geography of Syria. The Ottomans actually adopted “Syria” as the name for one of their Vilayets replacing the centuries-old designation of the region as “Esh Sham.” Through the influence of Christian Arab literature and Western European usage during the nineteenth century, the modern Arabic form of Syria, or “Suriya” came into regular usage, and by the end of the century it generally replaced Esh-Sham or Bilad al-Sham even in Muslim Arab usage. The Modern Nations, including Israel, were in reality all part of what would be better described as “Historic Syria” or its former equivalent, Esh-Sham, not “Historic Palestine,” a fact that is entirely lost in today’s discourse on the Middle East. An excellent depiction of how the region was commonly known as Syria is seen in Map F, published by French geographer Vital Cuinet in 1896, which shows the Vilayet of Syria and the Ottoman administrative units.

The local Arab population at the time would have also generally referred to the entire region as Syria and themselves as “Syrians” (or the earlier name Esh-Sham/Bilad al-Sham), as they had in successive Muslim empires for many centuries. This accurate memory of “Great Syria” lasted for decades, as expressed by Faiz El-Khouri, Minister of the Syrian Legation in Washington, in a speech he delivered to the United Nations General Assembly on May 14, 1947, regarding the Palestine question:

…I should like to explain to the General Assembly what the position of Syria is with respect to Palestine. I think most of you, if not all, know that Palestine used to be a Syrian province. Geographical, historical, racial and religious links exist there. There is no distinction whatever between the Palestinians and the Syrians and, had it not been for the Balfour Declaration and the terms of the mandate, Palestine would now be a Syrian province, as it used to be.[xiv]

An earlier example of the connection to Syria can be found in a resolution issued by the First Congress of the Muslim-Christian Association held in Jerusalem in January 1919, which was convened to choose Arab delegates for the post-World War I peace conference. The resolution stated, “We consider Palestine as part of Arab Syria as it has never been separated from it at any time. We are connected with it by national, religious, linguistic, natural, economic and geographical bonds.”[xv] There was a clear recognition that Palestine was an artificial creation by Christian Europe and the congress preferred to focus on the long standing designation of the region as Syria.

Of course of all these facts are lost in today’s discourse, with an obfuscation of the historical reality that a distinct Palestinian consciousness, both ethnically and geographically, only emerged in the twentieth century. Syria by far is the more accurate term that should be applied to the people and geography of the region if the word “historical” is going to be used.

The Formation of Modern Palestine

Palestine as a formal political entity came into existence as a result of actions taken by the principal allied powers after World War I at the San Remo Conference held in April 1920. The San Remo Resolution dated April 25, 1920, was the document that officially created a mandate for Palestine, with the British placed in control of the territory. The resolution specifically directed the “Mandatory,” in this case the British, to establish a national home for the Jewish people in the newly formed entity, based on the previously issued Balfour Declaration.

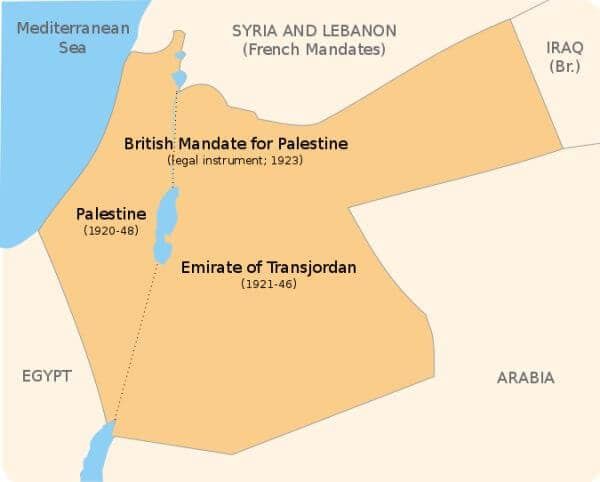

On July 1, 1920, the British implemented the agreements outlined in the San Remo Resolution and ended the military administration of the territory officially known as “Occupied Enemy Territory Administration” (“OETA”). Palestine was born. The initial borders of the Palestine Mandate, as agreed upon by the main powers in the region, Britain and France, included all of the territory that now comprises Israel, Jordan, the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. The British chose the name “Palestine” in line with Christian European tradition, again ignoring local terminology or Ottoman designations. As a concession to the Jewish population, and in acknowledgement of the Balfour Declaration, they added the initials “aleph” and “yud” (which stood for Eretz Israel, “Land of Israel”) to the Hebrew form of the name Palestine. Over the next three years, continued negotiations with the French and other regional events would lead to significant changes to the borders of the Palestine Mandate. These modified borders would eventually become the boundaries for the states of the Middle East today, and again, seemingly canonized as sacred historical borders.

During these discussions among the powers, for reasons beyond the scope of this article, the British unilaterally decided to carve out 77% of the Palestine Mandate as granted to the British at San Remo and place it under the control of Abdullah, naming him the new Emir of Trans-Jordan (See Map G). This new Arab entity, which was really always part of “Historic Palestine,” was officially born on April 11, 1921. As is often the case, this critical event in the geographic history of the region is typically ignored today. Most discussions of the conflict do not acknowledge that modern Jordan ethnically and geographically has always been the same as areas west of Jordan River.

Conclusion

It is difficult to separate the old reality from our modern terminology and organize the constantly changing place names. What adds to the confusion is the fact that Christian foreigners in the nineteenth and early-twentieth century decided to revive and maintain ancient territories and places names with boundaries, even though neither the actual political rulers of the territory nor the local inhabitants had any use for these place names. Here are the key conclusions that should become part of the discourse on the history of the region:

- Palestine was a provincial place name established by the Romans in 135 CE to replace “Judea” and all other vestiges of Jewish life in the region following the defeat of the Jewish rebellion. The Muslim conquerors in the seventh century maintained the name “Filastin” to refer to a province, but after the Christian conquest, the name fell out of use.

- The Muslim Mamelukes who defeated the Christians did not refer to any territory as Palestine/Filastin, and neither did the Ottoman Turks who controlled the region from the early-sixteenth century through World War I. For almost a millennium, the place name “Palestine” was not in use, a long-forgotten vestige of ancient Roman rule.

- The term “Palestine” was brought back into regular use by Christian Europeans in the 1800s due to its connection to the Bible and the land of Jesus. Neither the Ottoman Turks nor the local inhabitants of the region referred to the term “Palestine” at this time.

- Europeans created maps of “Palestine” in the nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries based on ancient biblical notions of this region and anachronistically placed them in modern atlases of the era, even though no such entity existed. The actual place names and boundaries of the region could be found in the same atlases under the proper heading “Turkey in Asia.” It would be as if Westerners today insisted on referring to Iraq as Historic Sumer and included maps of ancient Sumer in contemporary atlases, with no ancient maps for any other nation.

- Palestine during the Roman era, as displayed in maps create by Europeans in the nineteenth century, and in the formation of the Palestine Mandate in 1920 always comprised of territory both east and west of the Jordan River. It also included parts of southern Lebanon which historically was not distinct from areas in northern Israel. This is easily confirmed by numerous geographical surveys of the region undertaken in the nineteenth century, led by British geographers (e.g. The Palestine Exploration Fund published “An Introduction to the Survey of Western Palestine” in 1881, with Western Palestine ending at the Jordan river and Eastern Palestine on the other side).

- The Palestine Mandate placed under British control after World War I conformed to the fact that Palestine in all of its incarnations always included territory on both sides of the Jordan River.

- When the British unilaterally decided to create Trans-Jordan in 1921 with 77% of the territory of the original mandate, it maintained only 23%, the portion west of the Jordan River, under the name “Palestine.” Somehow in the decades after this separation, the notion of “Palestine” and “Historic Palestine” became confined only to portions west of the Jordan River.

- The 1947 Partition Plan which recommended a partition of Mandatory Palestine into a Jewish State and Arab state granted the Jewish state about 56% of the territory – but this comprised only 13% of the original Palestine Mandate. In fact, the Partition Plan effectively granted Arabs two states out of the Palestine Mandate comprising 87% of the original territory.

- After the 1948 War of Independence the new State of Israel expanded its territory to comprise about 78% of the reduced Palestine Mandate while the West Bank and Gaza totaled 22% of the area. Israel today comprises only 18% of the original Palestine Mandate.

- When Abbas says that the Palestinian people will accept a state on only 22% of the territory of “historic Palestine” for the sake of making peace he is grossly incorrect. Since Historic Palestine necessarily includes areas east and west of the Jordan River, as the original Palestine Mandate accurately reflected, the land comprising Jordan, West Bank and Gaza is 82% of the total today. Israel is a nation that ended up with a mid-teens percentage of the Palestine Mandate.

- Most people today use the post-1921 boundaries of the Palestine Mandate as their definition of “Historic Palestine” even though these artificially created boundaries are in fact an ahistorical, recent and artificial creation. “Mandatory Palestine” would be a more accurate term and should be adopted by the media instead of “Historic Palestine.”

- Forgotten in today’s discussion is that it would be far more accurate to call the region “Historic Syria” as geographically and ethnically the general region of today’s Israel, West Bank, Gaza, Jordan, Syria and Lebanon were part of one political entity originally known as Esh-Sham and later Syria. The local population would have also considered themselves part of this territory. If not for the revival of the name Palestine by Christian Europe sometime in the nineteenth century, Syria would have certainly won out as name of the region, as it had been for centuries. The quote above by the Minister of the Syrian Legation in Washington in 1947 makes this clear.

Salo Aizenberg, one of the leading collectors of Judaica picture postcards, is the author of Postcards from the Holy Land: A Pictorial History of the Ottoman Era, 1880–1918 and Hatemail: Anti-Semitism on Picture Postcards.

Liked this article? Follow HonestReporting on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and TikTok to see even more posts and videos debunking news bias and smears, as well as other content explaining what’s really going on in Israel and the region. Get updates direct to your phone. Join our WhatsApp and Telegram channels!

Join the fight for Israel’s fair coverage in the news

When you sign up for email updates from HonestReporting, you will receive

Sign up for our Newsletter:

Join the fight for Israel’s fair coverage in the news

Sources

Biger, Gideon. The Boundaries of Modern Palestine, 1840-1947 (RoutledgeCurzon, London, 2004).

Doumani, Beshara B. Rediscovering Palestine: Merchants and Peasants in Jabal Nablus (1700-1900, University of California Press, Berkeley, 1995).

Dowty, Alan. Israel/Palestine (Polity Press, Cambridge, 2005).

Hopkins, I.W.J. “Nineteenth-Century Maps of Palestine: Dual-Purpose Historical Evidence,” Imago Mundi (Vol. 22., 1968, p. 30-36).

Kark, Ruth, ed. The Land that Became Israel, Studies in Historical Geography (Yale University Press, New Haven, 1989). Entry by: Gideon Biger. “The Names and Boundaries of Eretz-Israel (Palestine) as Reflections of Stages in its History,” p. 1-22.

Le Strange, Guy. Palestine Under the Moslems, A Description of Syria and the Holy Land from A.D. 650 to 1500 (Alexander P. Watt, London, 1890).

Lewis, Bernard. Islam in History (Second Edition; Chapter Utilized: “Palestine: On the History and Geography of a Name,” p. 153-165) (Open Court, Chicago, 1993)

Mandel, Neville J. The Arabs and Zionism Before World War I (University of California Press, Berkeley, 1976).

Ma’oz, Moshe, ed. Studies on Palestine During the Ottoman Period (Magnes Press, Jerusalem, 1975). Entry by: Porath, Yehoshua. “The Political Awakening of the Palestinian Arabs and their Leadership Towards the End of the Ottoman Period,” p. 351-381.

MacCoun, Townsend. The Holy Land in Geography and in History, Vol II (MacCoun, New York, 1897).

Parkes, James. History of Palestine From 135 A.D. to Modern Times (Oxford University Press, New York, 1949).

Pitcher, Donald Edgar. An Historical Geography of the Ottoman Empire (E.J. Brill, Leiden, Netherlands, 1972).

Porath, Yehoshua. The Emergence of the Palestinian-Arab National Movement 1918-1929 (Frank Cass, London, 1974).

Richter, Julius. A History of Protestant Missions in the Near East (Fleming H. Revell Company, New York, 1910).

Zachs, Fruma. The Making of A Syrian Identity, Intellectuals and Merchants in Nineteenth Century Beirut (Brill, Leiden, 2005).

[i] Erekat, Saeb. Trump Doesn’t Want Peace. He Wants Palestinian Surrender. New York Times, May 22, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/22/opinion/trump-israel-palestinian-peace-plan.html

[ii] Berger, Miriam. “Palestinian citizens of Israel struggle to tell their stories,” Columbia Journalism Review, January 11, 2019. https://www.cjr.org/analysis/palestinian-citizens-of-israel-musawa.php

[iii] Cook, Jonathan. “The ‘Deal of the Century’ Would Force Palestinians to Swallow a Bitter Pill.” Washington Report on Middle East Affairs. June/July 2019, pp. 8-10. https://www.wrmea.org/2019-june-july/the-deal-of-the-century-would-force-palestinians-to-swallow-a-bitter-pill.html

[iv] (29 November 2012) Statement by President Abbas before the Adoption of resolution 67/19 on the Status of Palestine in the United Nations. http://palestineun.org/29-november-2012-statement-of-president-abbas-before-the-adoption-of-resolution-6719-on-the-status-of-palestine-in-the-united-nations/

[v] Dodd, Mead & Company, 1903

[vi] Sources for this section include Kark (Biger article), p. 15-18; Parkes, p. 87-88; Le Strange (p. 5 and 27); MacCoun, p. 107-109; Pitcher, p. 128 and 141; Zachs, p. 95-102; Lewis, p. 158.

[vii] Biger (Kark), p. 19.

[viii] Hopkins, p. 30, 36.

[ix] F.A. Brockhaus, Leipzig, 1892.

[x] Rand, McNally & Cos Enlarged Business Atlas, Chicago, 1892.

[xi] For example, see Dowty, p. 19.

[xii] Doumani, p. 261.

[xiii] Biger, p. 68

[xiv] United Nations General Assembly Seventy-Eighth Plenary Meeting (A/2/PV.78), held in the General Assembly Hall at Flushing Meadow, New York, May 14, 1947 at 3 p.m.

[xv] Porath, p. 82.