Zionism, at its root, is the belief that Jews have the right to self-determination and live in a state of their own by re-establishing a Jewish homeland in the Land of Israel. Jews, perhaps the ultimate refugees over history, understand what it means to be homeless and feel keenly the need to support others in their time of need. Never have the two clashed so obviously and openly as when a wave of African migrants arrived in Israel between 2006 and 2012.

Over the course of six years, a surge of approximately 40,000 African refugees and economic migrants entered Israel from across the Egyptian border. These asylum seekers are generally believed to be from Eritrea and Sudan, though it is difficult to prove with certainty.

The wave of immigration created a conflict within Israeli society. On one hand, Israelis were concerned over rising crime rates and the demographic character of Israel as a Jewish state, triggering support for deportation in some quarters. Meanwhile, well-attended protests against deportation highlighted Israel’s moral obligations to those in need.

Israel’s Response

Despite a historically tumultuous reputation, both Rwanda and Uganda have recently become models of African progress: with rapidly increasing safety and standards of living, GDP, and sharply declining poverty rates. For these reasons, Israel sought to strike a deal with the states in which thousands of migrants and refugees would be settled back in Africa.

However, unconfirmed reports indicate that upon arrival in Rwanda and Uganda, deportees landed into serious problems, including detention and arrest, insufficient legal documents from the Israeli government, stolen paperwork, demands for bribes, and even reports of human trafficking.

In short, Israel faces an unclear dilemma between the conflicting feelings of Israeli people, moral imperatives, and the country’s legal and practical needs.

On December 11, 2017, a law approved by the Knesset required that the Interior Ministry deport African migrants from Israel (reportedly to Rwanda and Uganda). Israel announced it would offer refugees $3,500 (USD) to leave the country or face imprisonment. However, the law was dogged by allegations that it violated international laws, and eventually the deportations were scrapped on April 23, 2018 after Israel failed to strike an emigration agreement with Rwanda and Uganda.

Instead, Israel announced plans to grant refugee status to hundreds of Sudanese refugees, and gave renewed visas to migrants with expired temporary residency permits, signalling a softening in its position. Israel also allocated 28 million Israeli shekels (approximately 8 million dollars) to social and economic programs for integrating the migrant community. On the other hand, a law requiring 20% of asylum seekers’ wages be paid into an account that can only be redeemed when they leave the country remained in place, a clear attempt to encourage migrants to leave Israel.

What Are Other Countries Doing?

Israel’s plan for dealing with asylum seekers has prompted a degree of media outrage, and claims of international law violations.

Ironically, the media have paid relatively little attention to a similar 2016 plan by German Chancellor Angela Merkel offering to pay some 158,000 rejected asylum seekers €1,000 (about $1,185) if they voluntarily return to their countries of origin, including Syria, Afghanistan and Iraq. Those refusing the incentive would face forced deportation. The UK has also enacted a similar program.

Join the fight for Israel’s fair coverage in the news

How Does Israel Measure Up?

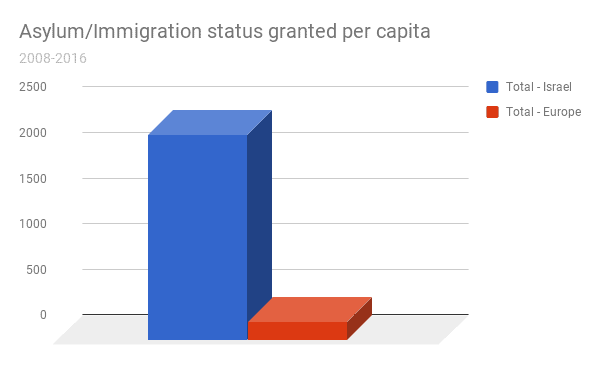

Israel takes in far more immigrants and asylum seekers per capita than most other countries, granting official status to 179,838 people from 2008 to 2016, (including many Jews in danger from Syria, Yemen and Ethiopia). This is not limited to Jews, but people in need globally. This is a staggering rate of 2,248 immigrants or asylum grants per capita (*per 100,000), over 10 times more than Europe at only 196 refugees per capita.

Put simply: Israel is one of the world’s smallest countries, yet accepts an enormous number of asylum seekers and immigrants relative to its population size. Israel also faces a unique demographic concern: it is the world’s only Jewish country, and some Israelis worry that a major population change could leave the world with no Jewish country at all. Relative to the country’s population, African migrants in Israel constitute a far bigger issue than that of migrants arriving in other states.

It is well known that Israel exercises a certain discrimination in its immigration policies: accepting Jews more readily than non-Jews. Less well known is that almost every other country does the same.

For example, in contrast to its relatively welcoming treatment of asylum seekers from Syria and Africa, the European Union has denied refugee status to 98.2 percent of the hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians fleeing the Russian invasion, and 70% have not even received partial protection.

Geography

Israel’s location makes it unique. Culturally and politically, it is in many ways a part of the West, but situated in a Mideast geography and with a border on north Africa.

Professor Ruth Gavison, from the Association for Civil Rights in Israel, explains that there is a well established difference between where exactly the asylum seekers are coming from (emphasis added):

…the entry of thousands of migrants who come from countries that do not share a border with Israel (and it is unclear whether they are labor migrants or asylum requesters), and a situation in which a small number of persons who escape an imminent danger that threatens them in their country adjacent to Israel arrive at the state borders.

Those who fled their homes from countries throughout the north, and the Horn of Africa, commonly chose Israel as their destination: usually passing entirely through the war-torn countries of Chad, Libya and Egypt (including the melting pot of terror groups in Egypt’s Sinai desert).

Asylum seekers passing through such countries run the risk of being enslaved, raped and tortured by human traffickers, as well as shot, or otherwise harmed by border guards.

Egypt, in particular, is a mainstream US ally, thus receiving large amounts of US foreign aid. It is bound by the same international laws as Israel and the rest of the world. The media, with all its focus on Israel, has generally failed to bring global attention to this horrifying situation.

Many Israelis are quick to point out that none of this changes Israel’s moral or legal obligations. At the same time, even if Israel’s situation merits criticism, the media have a professional obligation to present the story in proper global context: alongside the realities and questionable policies of both north Africa and the EU.

International Law

The international law on the topic of refugees is complex, and for the most part beyond the scope of this analysis. However, in order to fully appreciate the issues Israel faces, there are two important points to understand.

First, in order to enjoy refugee protections, an asylum seeker must be fleeing under a highly specific set of circumstances. And secondly, asylum granting states are never obligated to integrate refugees into their own country. On the contrary, relocating refugees in other countries is a common, and entirely legal practice, provided it is done safely and legally.

Yet international law must be implemented correctly. A letter written by a large group of notable Israeli academics objected to Israel’s current implementation, stating:

Detention of unlimited duration is aimed solely at breaking the detainee’s spirit. This constitutes a violation of international law, specifically as it pertains to human rights.

The question of whether Israel’s current practice violates international law is under deliberation within the High Court of Justice. In covering this story, the media have a duty to not merely echo the dramatic accusations of their peers and politicians, but to also note the complexities of this highly technical area of law.

What Next?

Professor Bernard Avishai writing in the New Yorker summarized Israel’s dilemma:

At the heart of the problem is…The absence in Israeli law of an inclusively democratic conception of citizenship, let alone democratic criteria for immigration.

Indeed, Israel’s laws regarding immigration have long focused primarily on aliya (Jewish immigration), with relatively little call for an organized asylum or naturalization process. Until now.

The wave of African migrants in Israel showed that the Jewish State faces a global asylum challenge, just like numerous other countries throughout the world. As such, Israel deserves the same pressure and criticism for failing to live up to expectations, yet also the same basic fairness enjoyed by all other countries that presently struggle with these moral, legal and practical dilemmas.

Featured image map by freevectormaps.com and protester by Yaniv Nadav/Flash90 with modifications; Kigali via YouTube/John Bern; Darfur CC-BY-SA Government Press Office;