The discovery of natural gas in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea is putting Israel on a collision course with Turkey. Israel is partnering with Cyprus and Greece to build an ambitious pipeline to Europe. But with billions of dollars at stake, Turkey is poised to play the spoiler.

What’s behind Turkey’s opposition, and how far will President Recep Tayyip Erdogan go to thwart Israel’s energy alliance?

Join the fight for Israel’s fair coverage in the news

The Pipeline

The EastMed pipeline is an undersea pipeline that will deliver natural gas in Israeli, Cypriot and Greek waters to Europe.

The roughly 2,000 km pipeline, comes with a $7 billion price tag and is due to be completed in 2025. It will initially transfer 9-12 billion cubic meters of gas annually, enough to meet an estimated 10 percent of Europe’s energy needs.

The pipeline will connect Israel’s Leviathan gas field with Cyprus’ Aphrodite field, continue to the Greek island of Crete and the eastern Peloponnese, then cross the Gulf of Patras before reaching mainland Greece. A second pipeline, known as Poseidon, will be laid to transfer the gas to Italy.

Greece, Cyprus and Israel Set to Sign EastMed Pipeline today https://t.co/4Lzk9qfbAE pic.twitter.com/xo0JknsFxy

— Greekcitytimes (@greekcitytimes) January 2, 2020

The gas sales will be a windfall for Israel, Cyprus and Greece.

Factoring in the Turkey’s Occupation

Turkey’s opposition to the EastMed pipeline must be understood in the context of its claims on Cyprus and current occupation of Northern Cyprus. Cyprus was an Ottoman territory until 1878, when Britain captured it during the Russo-Turkish war. During World War I, Cyprus was annexed to the British Empire after the Ottomans joined the Central Powers.

As the British Empire declined after World War II, a referendum was held in 1950; the island’s Greek Cypriot majority overwhelmingly voted for unification with Greece, while Turkish Cypriots preferred partitioning the island between Greece and Turkey.

In the 1950s, Greek Cypriot insurgents fought to oust the British from Cyprus. The London and Zurich agreements of 1959 set in motion Cypriot independence, which was finally attained in 1960. In 1961, the Republic of Cyprus became the 99th member state of the United Nations.

Turkey, notably, is the only UN member state that does not recognize Cyprus.

A constitution outlining the power sharing between Cyprus’ Greek and Turkish communities led to legal impasses and discontent on both sides. Tensions rose considerably when President Archbishop Makarios III proposed constitutional amendments in 1960, and violence between the two communities broke out in 1963.

But the conflict exploded in 1974, when Greece’s military junta ousted Makarios. Turkey invaded to protect Turkish Cypriots, and in the ensuing fallout, the Greek military regime collapsed. Amidst peace talks, the Turkish military launched the “Second Peace Operation” with a new invasion that overran Northern Cyprus. Almost all the Greek Cypriots there were driven off their lands or fled.

Today, Cyprus is divided by a UN-patrolled buffer zone. Nobody recognizes the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC), which is under international embargo in areas such as business, transportation, culture, sports and more. Thus:

- Northern Cyprus’ mail, trade, banking and transportation take place through Turkey.

- Turkish settlers from the mainland and their descendants “now make up roughly half the population in the north,” meaning they may already outnumber the original Turkish Cypriots and their descendants.

- An estimated 30,000-40,000 Turkish soldiers are stationed on Northern Cyprus andTurkish leaders want to establish a naval base there as well.

Meanwhile, the Greek Cypriot and Maronite communities, numbering 343 and 118 respectively as of 2014, live in enclaves and are denied the right to vote or run for office. Turkey is accused of erasing the Greek and Christian character of Northern Cyprus by neglecting and even looting archaeological sites, churches, and monasteries as well as Christian and and Jewish cemeteries.

(A comparison of Turkish settlements in Northern Cyprus with Israeli settlements in the West Bank is beyond the scope of this article. For more on that, Professor Eugene Kontorovich elaborates.)

War Over Energy Resources?

The Cyprus dispute has simmered for years. But the discovery of natural gas and other resources raised the stakes to include neighboring Mediterranean states. The Eastern Med gas rush began with the discovery of the Tamar and Leviathan gas fields in Israeli waters in 2009 and 2010 respectively. That prompted Israel and Cyprus to hammer out a maritime border agreement, just in time for the discovery of the Aphrodite gas field in adjacent Cypriot waters. Greece too, is exploring for gas and oil widely believed to be in the vicinity of Crete.

All this coincided with the steady rise of Turkey’s ruling Islamist neo-Ottoman AKP Party which wants to expand Turkey’s regional influence in Syria, Iraq, the Caucasus and, significantly, both Cyprus and various Greek islands in the Aegean Sea.

The bottom line is that the EastMed pipeline can’t be built without Cyprus, but Turkey doesn’t recognize Cyprus. And the Turks are throwing their weight around. Forbes explains:

Earlier this year, Turkey tested similar tactics the Chinese have used to impose control over the South China Sea. When experiments in using naval forces to escort Turkish drill ships into contested waters and to block rival petrochemical exploration vessels were met with little protest, Turkey simply moved the goalposts. Emboldened by somnolent America and European reactions, Turkey moved quickly to redefine the Mediterranean’s maritime borders. Earlier this month, Turkey concluded a massive maritime land-grab, entering into a maritime border agreement with Libya’s besieged government that cedes much of the resource-rich eastern Mediterranean to Turkish control.

For Turkey, regional maritime might is proving to be right.

A number of incidents have incidents have largely flown beneath the Western media’s radar, but point to a pattern of Turkish behavior that cannot be ignored:

- An Israeli research vessel, the Bat Galim, was working in Cypriot waters in coordination with the Cypriot government when it was was harrassed and forced away by Turkish naval ships in December 2019. (Israel responded two weeks later with Air Force jets circling over a Turkish research ship operating near Cypriot waters.)

- Turkey deployed armed aerial drones to Cyprus to further enforce its maritime claims.

- On January 14 alone, Turkish F-16 jets committed 91 violations of Greek air space including mock dogfights with Greek fighter jets and flying over inhabited areas of the Greek Islands.

- Turkey and Libya’s Government of National Accord (GNA) signed a maritime agreement creating an exclusive economic zone from Turkey’s southern Mediterranean shore to Libya’s northeast coast. Although the GNA has international recognition, it controls only limited amounts of the countryside, which is why Turkey is sending troops to Libya. Cyprus, Greece, Israel and Egypt denounced the agreement as illegal. There are concerns that Turkey’s endgame in Libya is to install a Muslim Brotherhood regime.

- Turkey is building its first aircraft carrier which is expected to enter service in 2021.

Indeed, Israel’s military “added Erdogan’s aggressive policies in the region to its list of ‘challenges’ in an annual assessment for the coming year,” the first time the IDF assessed Turkey this way.

Israel has other reasons to be wary of Erdogan and the ruling AKP Party.

- Erdogan allows Hamas to plot terror attacks on Israel from Turkish soil.

- Turkish meddling in Jerusalem undermines Israeli sovereignty over the city.

- Hoping to undercut Jewish land claims, Erdogan transferred to the Palestinians thousands of Ottoman-era land registries.

Other Eastern Med Players

While Israel, Cyprus and Greece have been quickest to capitalize on their bonanza of natural resources, they aren’t the only Eastern Med countries with offshore gas carefully watching how matters play out with Turkey:

- For the Palestinians, the Gaza Marine gas field remains undeveloped because of the geopolitical headaches posed by Hamas control over the Strip.

- In Egypt, sales from the Zohr natural field have had little trickle-down effect on the public and Cairo actually imports Israeli gas.

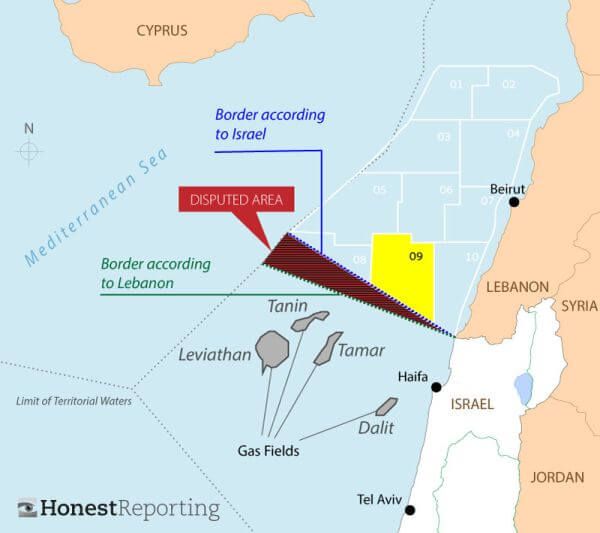

- Lebanese efforts to exploit offshore resources have been slow due to government inefficiency and political paralysis. The Israeli-Lebanese maritime border is also a matter of contention, with reserves extending into a disputed zone. Hezbollah has threatened to fire missiles at Israeli gas rigs.

Related reading: Understanding the Israel-Lebanon Maritime Border Dispute

Turkey’s attacks on US-backed Kurds, purchase of Russian missile systems, support for Islamist factions in Syria, and championing the Palestinian cause suggest Ankara wants to actively expand its regional influence in conjunction with Iran and Russia — at the expense of the US, the West and Israel.

Will Turkish expansionism lead to wider conflict?

Only time will tell.

Enjoyed reading this article? Follow the Israel In Focus page on Facebook to read more articles explaining Israel’s history, politics, and international affairs. Click here to learn more!

Images: Cyprus map via Wikimedia Commons with additions by HonestReporting; Nicosia CC BY-NC-ND Marco Fieber; Turkish navy via YouTube/Turk Silahali Kuvvetleri;