Israel’s War of Independence isn’t so well-understood in the West. The prevailing narrative is probably best articulated by the late US comedian, Alan King, who said, “A summary of every Jewish holiday: They tried to kill us, we won, let’s eat!”

But a closer look at the war sheds light on a number of controversies still unsettled since the Israeli state’s founding in 1948.

Israel’s critics spin the War of Independence as the original sin of the Jewish state’s creation. They twist the history and hold the state to impossible standards, even as the Jews fought for their lives. All for the sake of smearing Israel with claims of atrocities and ethnic cleansing, and using the post-war armistice lines to prejudice peace efforts ever since.

The War of Independence was Israel’s deadliest war. According to the figures, on the Israeli side, 6,373 people were killed — about one percent of the Jewish population, though this number also includes new immigrants and foreigners. Estimates put the Arab death toll at 10,000.

Join the fight for Israel’s fair coverage in the news

The players

The Yishuv: This was the organized Jewish community of the Holy Land during the Ottoman and British Mandate periods. In the years leading up to independence, its leader was David Ben-Gurion.

Israeli history sometimes distinguishes between the “Old Yishuv” and the “New Yishuv.” The Old Yishuv refers to the community of Jews who pre-existed the waves of aliyah that began in the 1880s. The New Yishuv refers to Jews who immigrated from Europe in those pre-state years. The Old Yishuv was religious and lived primarily in Jerusalem, Hebron, Tiberias and Safed. The immigrants of the New Yishuv tended to be more secular and socialist; they founded many of the towns, rural villages and cooperatives (kibbutzim). The Haganah, the main underground defense militia, was founded by the Yishuv (more on that below).

The Arab Higher Committee: This was the primary leadership of the Palestinian Arabs. It was made up of various political and clan leaders and headed by the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Haj Amin-al Husseini. Following the assassination of a British official in 1937, the Mandate administration banned the committee; several of its leaders were deported or fled into exile, including the Mufti. After World War II, the AHC was reconstituted and even recognized by Mandate authorities.

The committee rejected all compromise with the Jews, demanding a complete end to all Jewish migration, a halt in the sale of land to Jews and the cancellation of the Balfour Declaration and the British Mandate. After the War of Independence, Jordan banned the AHC from the West Bank.

Related reading: In Focus: How The UN Partition Plan Led to Israel’s Birth

The UN partition plan of 1947 was accepted by the Yishuv but rejected by the Arab Higher Committee.

Origins of the IDF

The origins of today’s Israel Defense Forces lie in the Haganah, an underground military organization created by the Yishuv. (Haganah literally means “defense.”) Following deadly Arab riots in Jerusalem and Jaffa in 1920 and 1921 respectively, Yishuv leaders concluded that the officials of the British Mandate had no interest in confronting the Arab gangs responsible for the violence. The original militias were localized farmers with minimal arms or training.

After the Arab riots of 1929, the Haganah’s organization and responsibilities expanded significantly, with more recruits, especially from the cities now, and better weapons.

Related reading: Did Arab Violence Really Start With the ‘Occupation’?

Two weeks after Israel declared its independence, the Haganah was disbanded, and its forces merged with fighters from smaller, rival underground revisionist militias (mainly the Irgun and the Lehi) to create the Israel Defense Forces. (The relationship between the Haganah and the revisionists is beyond the scope of this article. See the Jewish Virtual Library for more on the Irgun, the Haganah’s Hunting Season and the Altalena Affair.)

Crucially, the rivalries didn’t spiral into an open civil war between Jews. During the War of Independence, the IDF seamlessly became Israel’s only armed force and subordinate to the elected government.

The War of Independence itself

The War of Independence is best understood in two phases: First, as a Jewish-Arab civil war, then a regional war.

The civil war between the Arabs and the Yishuv began on November 29, 1947. Following the United Nations vote to partition Palestine into separate Jewish and Arab states, Palestinian Arabs attacked numerous Jewish communities and neighborhoods. Arab volunteers from neighboring countries increasingly joined the conflict; over the next four months, the Yishuv suffered severe casualties.

The tide began to turn in April, 1948 when the Haganah took the initiative. In a period of six weeks, Jews captured the Arab areas of Haifa, Tiberias, Acre and and Safed. Much of the land designated for a Jewish state by the UN partition plan came under Yishuv control during this time. The Haganah also managed to open the road to Jerusalem, albeit temporarily. (The controversial capture of Deir Yassin, in the hills outside Jerusalem, was during this period.)

The War of Independence changed from a civil war to a broader regional war in May. In a nutshell, Israel declared independence on May 14. The next day, the last British personnel departed and the armies of Egypt, Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, and Iraq immediately invaded. These five armies had superior numbers and were better armed. The IDF suffered early defeats, losing the Etzion bloc south of Jerusalem to Jordanian forces, the northern community of Mishmar HaYarden to Syrian forces, and Yad Mordechai near Gaza to Egyptian forces.

But by July, the IDF stemmed its losses, and in October, launched the first of four operations that paved the way for an armistice:

- Operation Yoav (October): Clearing the road to the Negev and capturing Beer Sheva.

- Operation Hiram (October): Capturing the Upper Galilee from the Arab Liberation Army.

- Operation Horev (December): Trapping the Egyptian army in Gaza.

- Operation Uvda (March, 1949): Driving Jordanian forces out of the southern Negev, reaching Eilat and the Red Sea.

The armistice and the Green Line

The war ended with a series of armistice agreements in 1949, signed by Egypt (February 24), Lebanon (March 23), Jordan (April 3) and Syria (July 20). Iraq withdrew its forces and handed over its sector to the Arab Legion of Jordan without signing any armistice. Israel would go on to seize the West Bank, Golan Heights and Gaza Strip in 1967 during the Six Day War, a defensive war fought after Egypt closed the Straits of Tiran and massed forces along its borders.

The international community regards these 1948 lines as Israel’s borders, viewing the West Bank as Palestinian territory. But Professor Eugene Kontorovich explains that international law does not treat the War of Independence’s armistice lines as an actual border:

The “Green Line” was created in the wake of Israel’s 1948-49 War of Independence. Upon the country’s founding, Jordan and its allies invaded, with the goal of preventing the creation of a Jewish state. Although they failed at that goal, the Arab armies did occupy significant territory when the armistice was called, including what is now widely referred to as the West Bank and East Jerusalem. Jordan subsequently expelled all Jews from the areas under its control.

In 1967, during the Six Day War, Israel recaptured these places. But in the war’s aftermath the United Nations invested the temporary 1949 armistice line with talismanic significance. The U.N. claimed Israel was “occupying” the territory that Jordan had forcibly seized not two decades earlier. Thus the international community came up with a unique demand: Israel had to keep the areas under its control, including East Jerusalem and the Old City, free of Jewish inhabitants. Any move to unify Jerusalem would be considered a war crime.

In international law, armistice lines are not borders; they merely mark breaks in the fighting. The claim that the Green Line created a permanent “Judenrein” zone in the area occupied by Jordan, or that it in any way changed the legal status of the territory on the far side, is unique and illiberal.

Aside from the borders, the 1949 armistices paved the way for Israeli membership in the UN. The UN Security Council rejected the fledgling state’s initial membership bids in May and December of 1948, saying Israel couldn’t prove its viability. But Israel reached an reached an armistice with Egypt and was closing in on one with Lebanon, providing the opening for the Security Council’s recommendation. By the time the UN General Assembly voted, Israel had reached an agreement not only with Lebanon, but Jordan too.

Thus, on May 11, 1949, the UN General Assembly admitted Israel as a member by a vote of 37-12, with nine abstentions.

The War of Independence technically ended with the final Syrian armistice on July 20. But the fallout was just beginning.

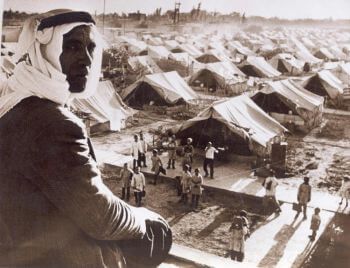

Refugees of the War of Independence

The number of Palestinian Arab refugees created by the War of Independence isn’t clear. A 1948 UN report put the number at 360,000. Findings from Israel’s 1949 census suggest that no more than 650,000 Palestinians could have become refugees. The Arabs put the number of refugees in the 800,000-1,000,000 range. The vast majority of the Arab inhabitants left by choice, as Mitchell Bard explains:

Anticipating war, thousands of Palestinian Arabs fled their homes

The Palestinians left their homes in 1947-48 for a variety of reasons. Thousands of wealthy Arabs left in anticipation of a war, thousands more responded to Arab leaders’ calls to get out of the way of the advancing armies, a handful were expelled, but most simply fled to avoid being caught in the cross fire of a battle. Had the Arabs accepted the 1947 UN resolution, not a single Palestinian would have become a refugee and an independent Arab state would now exist beside Israel . . .

By the end of January 1948, the exodus was so alarming the Palestine Arab Higher Committee asked neighboring Arab countries to refuse visas to these refugees and to seal the borders against them.

Meanwhile, Jewish leaders urged the Arabs to remain in Palestine and become citizens of Israel.

Related reading: The Forgotten Jewish Refugees From Arab Lands

The number of Palestinian Arabs fleeing their homes rose in April and early May as the Haganah captured Haifa, Tiberias, Acre and Safed. The Yishuv tried to persuade the Arabs to stay and carry on their lives, but most chose to leave, not wanting to be judged as traitors.

Expulsions by force were limited to the areas of Ramle and Lod because Arab forces used those towns as bases for frequent attacks on Jewish convoys and nearby communities. And Palestinian Arabs in some villages near Lake Hulah in the Galilee were “encouraged” to voluntarily evacuate due to psychological warfare employed by the Palmach, the Haganah’s elite fighting force.

Bard explains:

As was clear from the descriptions of what took place in the cities with the largest Arab populations, these cases were clearly the exceptions, accounting for only a small fraction of the Palestinian refugees. The expulsions were not designed to force out the entire Arab population; the areas where they took place were strategically vital and meant to prevent the threat of any rearguard action against the Israeli forces, and to insure clear lines of communication. [Benny] Morris notes that “in general, Haganah and IDF commanders were not forced to confront the moral dilemma posed by expulsion; most Arabs fled before and during the battle, before the Israeli troops reached their homes and before the Israeli commanders were forced to confront the dilema” (The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited, MA: Cambridge University Press, 2004, p. 592).

Related reading: The UNRWA Controversy Explained

A letter by historian Benny Morris puts the refugee problem in perspective:

The displacement of the 700,000 Arabs who became “refugees” – and I put the term in inverted commas, as two-thirds of them were displaced from one part of Palestine to another and not from their country (which is the usual definition of a refugee) – was not a “racist crime” (David Landy, January 24th) but the result of a national conflict and a war, with religious overtones, from the Muslim perspective, launched by the Arabs themselves.

There was no Zionist “plan” or blanket policy of evicting the Arab population, or of “ethnic cleansing”. Plan Dalet (Plan D), of March 10th, 1948 (it is open and available for all to read in the IDF Archive and in various publications), was the master plan of the Haganah – the Jewish military force that became the Israel Defence Forces (IDF) – to counter the expected pan-Arab assault on the emergent Jewish state. That’s what it explicitly states and that’s what it was. And the invasion of the armies of Egypt, Jordan, Syria and Iraq duly occurred, on May 15th.

See a separate article by Morris debunking in more detail claims of a Zionist “master plan” to expel and ethnically cleanse Israel of its Arab population through the War of Independence.

* * *

With the resolution of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict elusive as ever, it’s worth reminding ourselves of what happened and how the situation got to this point. An honest look at the historical record, especially the War of Independence, would go a long way in helping Israelis and Arabs come to terms, and help the world make better judgments to advance peace.

Featured image: via Wikimedia Commons; Ben-Gurion BY-NC Israel Defense Forces; refugee via Wikimedia Commons;

Before you comment on this article, please note our Comments Policy. Any comments deemed to be in breach of the policy will be removed at the editor’s discretion.