“It’s Israel’s fault the Palestinians can’t vote.” That’s an accusation we often hear, especially when Israel pivots to election campaign mode.

Unfortunately, the Palestinians are disenfranchised.

But not by Israel.

The Palestinians have been disenfranchised by their own feuding leaders in Fatah and Hamas. A look at the history shows Egypt and Jordan bear some responsibility too.

Join the fight for Israel’s fair coverage in the news

The Pre-Oslo History

The first election held in what would become the state of Israel was organized by the British Mandate in 1923. Jews and Arabs were to vote for members of an electoral college which would choose members of a 23-seat legislature. But Arabs boycotted the vote in a dispute over the distribution of seats; British authorities later annulled the results.

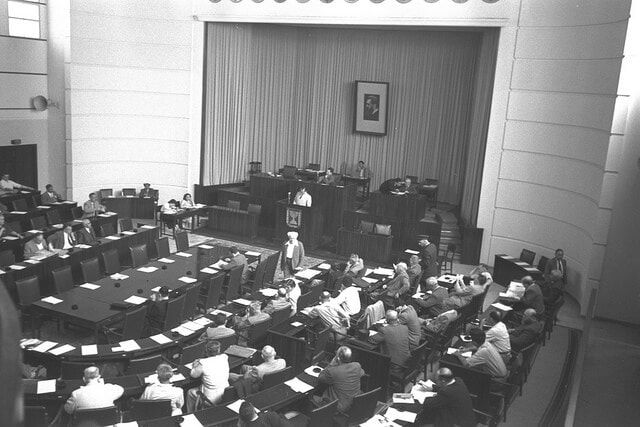

Britain quit the Holy Land in 1948, prompting Israel’s War of Independence. When that conflict finally ended, Israel was in control of the Negev, the Mediterranean coast, the Galilee plus the western half of Jerusalem. Arabs in those areas who did not flee the fighting became Israeli citizens, receiving full voting rights. The first Knesset included three MKs from an Arab party called the Democratic List of Nazareth, while a fourth Arab MK was with the Israeli Communist Party (more commonly known by its Hebrew acronym, Maki).

The Arabs who lived in the West Bank when the war ended came under Jordanian jurisdiction, while Arabs living in Gaza lived under Egyptian military occupation. The roughly 700,000 Arabs who fled to neighboring countries — the first Palestinian refugees — came under the administration of the UN Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA). Neither Syria nor Lebanon ever offered citizenship to any Palestinian refugees or their descendants. Egypt offered citizenship to 50,000 Palestinians with Egyptian mothers — in 2012.

Jordan, on the other hand, annexed the West Bank in 1948, a move that was never internationally recognized. Palestinians who fled to Jordan during the war obtained full Jordanian citizenship. After the war, in the West Bank, some Palestinians procured Jordanian citizenship but most did not. In Jordan’s 1950 general election, Palestinians sent 20 “West Bankers” to represent them in the new parliament in Amman. (Palestinians who fled to Jordan during the 1967 war did not receive Jordanian citizenship, just special passports allowing them to travel abroad.) However, in the 2000s, reports disclosed that Amman was revoking the Jordanian citizenship of thousands of Palestinians — including Mahmoud Abbas. Jordanian officials never explained how many were actually withdrawn or why.

Related reading: How Do Israeli Elections Work?

As for Gaza, following the War of Independence, the “All-Palestine Government” served as the Strip’s figurehead government. It only existed under the protection of the Egyptian military administration which ran Gaza’s day-to-day affairs. (Egyptian President Gamel Abdel Nasser disbanded the All-Palestine Government in 1959, in the name of “Pan-Arabism.”)

Perhaps foreshadowing the current tensions between the West Bank and Gaza, Egypt didn’t trust Jordan’s influence over the West Bank; the Jordanians were suspicious of Egypt’s domination over the All-Palestine Government.

During the Six Day War of 1967, Israel captured Gaza and the West Bank, including Jerusalem’s eastern neighborhoods, becoming responsible for managing the daily affairs of these areas.

In accordance with international law, Israel established a military administration in those areas, while extending Israeli law to eastern Jerusalem. (In 1980, the Knesset would further enshrine the city’s unified status with the Jerusalem Law, which declared the united city as Israel’s capital.) By extending Israeli law to Jerusalem’s eastern neighborhoods, Israel obligated itself to give voting rights to the Palestinians living there. Israeli policy is make citizenship available to eastern Jerusalem Palestinians who apply for it, but will not impose citizenship on them. (More on Jerusalem voting below.)

Israeli attempts to organize West Bank municipal elections in 1972 and 1976 met with limited success.

Palestinians Vote: Oslo to Now

Just as Israeli citizens vote in Israeli elections, Palestinians vote in Palestinian Authority elections, which were set up within the framework of the 1993 Oslo accords (see Annex I).

The new Palestinian exercise in democracy began in 1996, when they elected Yasser Arafat as president with 88 percent of the vote. Palestinians also gave Fatah 55 of the 88 seats on the Palestinian Legislative Council (PLC). Palestinians living in eastern Jerusalem also voted, though Israel was not obligated to allow it. (However, those with full Israeli citizenship were not allowed to vote.) Also, the Palestinian diaspora — most notably those living in refugees camps abroad were also ineligible.

Palestinians didn’t hold another national election until January, 2005. A few months after Arafat’s death, Mahmoud Abbas was voted president with a majority of 62%. Abbas was widely viewed as Arafat’s natural successor and a leader Israel could do business with.

The PLC was expanded to 132 seats; the parliamentary elections of January, 2006, led to shocking results. Hamas won big, taking 74 seats, compared to Fatah’s 45. Fatah, for the first time, faced a real challenge to its political primacy.

Indeed, in June, 2007, lip service to normal political activity flew out the window when Hamas violently seized control of the Gaza Strip.

Fatah responded by entrenching itself in the West Bank. The Palestinian Legislative Council stopped meeting. Mahmoud Abbas, whose four-year term expired in 2009, simply continued as PA president. No national elections have been held since. In December, 2018, Abbas announced his intention to dissolve the parliament.

On the local level, Palestinians held several rounds of voting in municipalities to appoint mayors and members of town councils in 2005. However, by December, the balloting was not completed. The issue was put on hold as Fatah-Hamas disagreements increased.

Another attempt was made with local elections scheduled for July, 2010. Balloting was delayed two years when Fatah couldn’t agree on its own candidate list. Municipal elections due to be held in October, 2016, were suspended by a Palestinian Authority court. Voting eventually took place in May, 2017, but because of Hamas-Fatah feuding, the majority of West Bank locales held no elections.

There’s no end in sight to their impasse. With both wielding a veto power over balloting that isn’t to their advantage, many question whether either Fatah or Hamas really want national unity.

The Israeli government’s position? PA elections are a domestic Palestinian affair. It’s up to the Palestinians to break their political deadlock and choose their leaders.

Even if Israeli officials have preferences for particular people or parties, they know better than to express them. Any Israeli endorsement — real or implied — could be a kiss of death in Palestinian politics.

So just as Israelis don’t participate in Palestinian Authority elections, Palestinians don’t participate in Israeli elections. Nobody can participate in both elections. Full stop (almost).

The Jerusalem Exception

Although Palestinians are not entitled to participate in Israeli elections, eastern Jerusalem Palestinians vote in the city’s municipal elections, and even run for the city council. Or at least they’re entitled to. As explained earlier, Israeli policy is make full citizenship available to eastern Jerusalem Palestinians who wish to apply; this would let Palestinians vote and run in national elections as naturalized Israelis. In practice, the vast majority don’t apply, though there are periodic surges. Israeli policy is not to impose citizenship.

Although Palestinians are not entitled to participate in Israeli elections, eastern Jerusalem Palestinians vote in the city’s municipal elections, and even run for the city council. Or at least they’re entitled to. As explained earlier, Israeli policy is make full citizenship available to eastern Jerusalem Palestinians who wish to apply; this would let Palestinians vote and run in national elections as naturalized Israelis. In practice, the vast majority don’t apply, though there are periodic surges. Israeli policy is not to impose citizenship.

By law, only an Israeli citizen can be mayor, so it’s theoretically possible that Jerusalem could have an Israeli-Arab mayor with a council featuring non-Israeli Palestinians. With around 300,000 Palestinians eligible to vote in the 2018 municipal elections (about 40 percent of the population), there’s plenty of clout to reshape city politics.

Related reading: Deal With It: Jerusalem is Israel’s Capital

However, Palestinian residents of eastern Jerusalem historically boycott the local elections, saying participation legitimizes Israel control over the city. The boycotts are reinforced by fatwas (religious decrees) and intimidation.

The few Palestinians who buck consensus by throwing their hat in the ring never garner enough support. A Palestinian list called “Jerusalem, My Town,” led by Ramadan Dabash managed to get 3,001 votes in 2018. But to receive one of the city council’s 30 seats, his list would have needed 8,086 votes.

Nobody’s compelled to vote, but it’s disingenuous for Palestinians to then claim that city hall discriminates against them on issues like schools, garbage collection, health clinics etc. These issues do not stem from racial discrimination but rather from a simple lack of representation.

The Context of “Occupation”

It’s sometimes claimed that the Israeli “occupation” makes it impossible for Palestinians to have truly free elections. It’s commonly argued that checkpoints hinder freedom of movement for lawmakers, candidates and activists. Many Palestinian lawmakers are in Israeli prisons. And Israel restricts Palestinian political expression in Jerusalem. How can Palestinians vote under these circumstances?

While the legalities of occupation are beyond the scope of this work, the Israeli “occupation” is not illegal. In fact, it’s required by international law. “Occupying powers” are obligated to oversee territory by a military administration, not a civilian one. The occupation is supposed to be temporary, for the sake of law and order, until the territory’s political status is resolved. (For a better understanding, HonestReporting’s Daniel Pomerantz elaborated on this point.)

After the Six-Day War, Israel offered to return the captured territory to the Arabs for an end of hostilities. In August, 1967, Arab leaders met in Khartoum to coordinate a response to Israel’s sweeping land-for-peace offer. It became known as The Three Noes: No peace with Israel, no negotiations with Israel, and no recognition of Israel.

Related reading: Three Noes That Set the Mideast On Course of Conflict

It took years for those Noes to soften. The process that created the Palestinian electoral process also recognized the presence of Israeli security forces. Unfortunately, checkpoints are necessary to stop terrorists. Sadly, Palestinians have elected lawmakers associated with terror groups, which is why many are imprisoned. This phenomenon’s poster boy would be Hebron Mayor Tayseer Abu Sneineh, who in 1980 was convicted of murdering six Israelis and released in a 1983 prisoner swap.

As for restrictions on political activity in Jerusalem, that’s what Palestinians agreed to in the 1993 Oslo 2 agreement (see Article XVII (1a)).

Ignored is the Palestinian diaspora. Refugees living in UNRWA camps abroad face varying restrictions on employment, property ownership, as well as the right to participate in their host country’s elections. This is an issue for every refugee population, but the Palestinians are unique in terms of the extended stalemate over their status and how the UN defines and supports them.

Related reading: The UNRWA Refugee Controversy Explained

Contrast the three million disenfranchised Palestinians living in Jordanian, Lebanese and Syrian refugee camps with naturalized Palestinians living in far-flung but vibrant communities including Chile, Honduras, Germany and the US. For example, in November, 2018, Rashida Tlaib made international headlines for becoming the first Palestinian-American woman to win a seat in the US Congress.

“Occupation” is a convenient word to lay blame on Israel’s doorstep. But the combination of Hamas-Fatah enmity, ineptitude and indifference is what really disenfranchises Palestinians.

Liked this article? Follow HonestReporting on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and TikTok to see even more posts and videos debunking news bias and smears, as well as other content explaining what’s really going on in Israel and the region.

Featured image: vectors by Vecteezy; Knesset CC BY-NC-SA Government Press Office; Hussein and Nasser via Wikimedia Commons; Abbas via President of Russia; Gaza takeover via YouTube/AP Archive; Abu Sneineh via YouTube/Good Afternoon NET;