The latest from my inbox. The bolding is mine.

From: …@bigpond.net.au

Date: Mon, Nov 13, 2017 at 11:53 AM

Subject: Court Action

Thank you for all your articles on the continuous bias in the media towards Israel

I think it’s time to increase pressure on the individual media publishers by taking heavy legal action in the courtroom, it is obvious that winning pathetic apologies is a waste of time.

There may have been some court action before, but I would like to see a huge increase in legal activity suing publishers and editors for millions of dollars on the grounds of unethical reporting and racism. They need to be hit hard so they will think twice before misreporting

I’m sure the Worldwide Jewish Community has the legal minds and finance to set up a fighting fund to stop this rot

Please let me know your thoughts

* * *

Thanks for writing. This is something we’ve discussed in the past. Suing journalists or news services is no simple matter.

First of all, Western free speech laws are very strong, meaning that a plaintiff would have to be able to demonstrate that the news coverage in almost any case was an outright lie. Period. Misleading coverage that has enough truth to it wouldn’t be actionable in a court of law. (Legal beagles can hash out the details in the comments section.)

Second of all is the question of who has “standing” to sue? Standing refers to who has the right to sue because they were directly harmed. The vast majority of the problematic media coverage we see is biased against the state of Israel, not against specific people.

Join the fight for Israel’s fair coverage in the news

In any event, states don’t file defamation lawsuits against foreign journalists for three reasons:

1. Countries with free speech laws enforce defamation against individuals more strongly than defamation against organizations. That distinction makes it prohibitive for Israel to theoretically take legal action against a media service. In many jurisdictions, states are prohibited from suing over defamation at all.

2. Jurisdiction is thorny. Even if Israel were to take legal action against a foreign news outlet, should the lawsuit be filed in Israel, the home state of the news service, or perhaps the area where the corporate headquarters are? It depends on where the media outlet’s money is located and whose free speech rules would be most advantageous.

3. States have other means at their disposal to fight problematic news. States can withhold or withdraw press credentials (like when Israel suspended, then restored credentials for Al Jazeera’s bureau chief) or even boycott journalists (such as in 2003 when Israel prohibited government officials from appearing on BBC shows, though the news service was not barred from press conferences.)

Boycotting a journalist or news service is a powerful card to play because for the media, access is everything. There are also potential diplomatic channels for political leaders to contact the highest level news executives.

What about individuals suing the media?

For one thing, you need a clear-cut plaintiff who has suffered as a result of sloppy media coverage, and who has the finances and fortitude to wage a lengthy legal battle whose outcome is by no means certain. Such lawsuits aren’t common, but two come to mind.

One was filed by the late Ariel Sharon against Time. In 1983, the magazine falsely reported that Sharon, then the Minister of Defense, had encouraged Lebanese Phalangists to massacre Palestinians living Beirut’s Sabra and Shatila refugee camps after the assassination of Lebanese president Bashir Gemayel.

Sharon and Time reached an out of court settlement in 1986 in which Time paid an undisclosed but reportedly “substantial” sum. Under the terms of the settlement, Time also admitted that the description of Sharon’s alleged conversations with Phalangists in Beirut was “erroneous.”

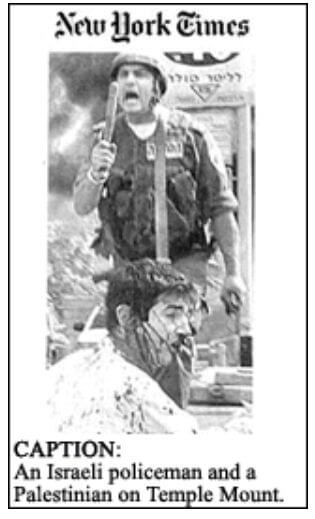

More recently was a lawsuit against Associated Press and the French paper, Libération over a September, 2000 photograph that incorrectly described US student Tuvia Grossman — who had been rescued from a Palestinian lynch mob — as a Palestinian.

More recently was a lawsuit against Associated Press and the French paper, Libération over a September, 2000 photograph that incorrectly described US student Tuvia Grossman — who had been rescued from a Palestinian lynch mob — as a Palestinian.

A Paris judge in 2002 ordered the two news services to pay Grossman 4,500 Euros in damages for misrepresenting him. You can read more about Grossman’s story how it played into HonestReporting’s founding by seeing The Photo That Started It All.

In one other instance, the mere threat of legal action was enough to make a difference.

In May, 2012, The Guardian wrote that Tel Aviv was Israel’s capital. When HonestReporting complaints to both The Guardian and the UK’s Press Complaints Commission were rejected, HonestReporting threatened legal action. In the end, The Guardian backed down, making a retraction and revising its style guide.

As for your comment that “winning pathetic apologies is a waste of time,” I don’t agree. An apology is simply an admission of error, but for legal purposes, an apology typically includes a stated or implied plea for forgiveness. It may be accompanied by a financial payment of one form or another as well.

Moreover, just as info, quotes, headlines, photos, videos, podcasts, etc. are “on the record,” so are the corrections. And in the internet age, anyone can get online and see, for example, what NPR had to say about a map error, how the International Business Times handled a grossly inaccurate Temple Mount report (the story was removed from the web site), or whether The Independent retracted a story 10 years ago accusing the IDF of using uranium shells in Lebanon (UN atomic experts debunked the claim but editors never retracted it).

So yes, apologies are part of the process of holding the media accountable.

Sometimes, legal action is both an appropriate and practical option. In the past, relevant parties, including HonestReporting, have gotten involved in such battles. However, the Western world generally accepts that freedom of speech is such a high priority that legal action for biased news is rendered impractical or even impossible.

That’s why HonestReporting has developed advocacy skills for readers and relationships with journalists. Sometimes the best remedy for biased speech is more and better speech in return.

Daniel Pomerantz contributed to this post.

Featured image: Vector by freedesignfile; Sharon CC BY-NC-SA Government Press Office;